Two Iraqi refugees were sent to federal prison in the Bowling Green, Kentucky terrorism case for scheming to help Al-Qaeda murder U.S. soldiers in Iraq.

The men, Iraqi citizens who spent time in Syria, did not commit a “massacre” on U.S. soil (Donald Trump’s adviser Kellyanne Conway used that word on television), but they were accused of conspiring to blow up American service members in Iraq with weapons of mass destruction (IEDs). A government sentencing memo says one of the men confessed he had used IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices) “hundreds of times” in Iraq.

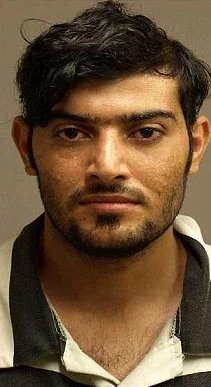

Mohanad Shareef Hammadi, 25, and Waad Ramadan Alwan, 41, never managed to carry out the schemes they hatched once they found haven in Kentucky because the feds had infiltrated their circle. However, the sentencing memo says Alwan confessed that, back in Iraq, “he twice blew up Bradley tanks, and on one occasion participated in an attack that killed U.S. soldiers.” Hammadi, who immigrated to the United States in 2009, applied for refugee status after traveling from Iraq to Syria, a sentencing memorandum in his case says.

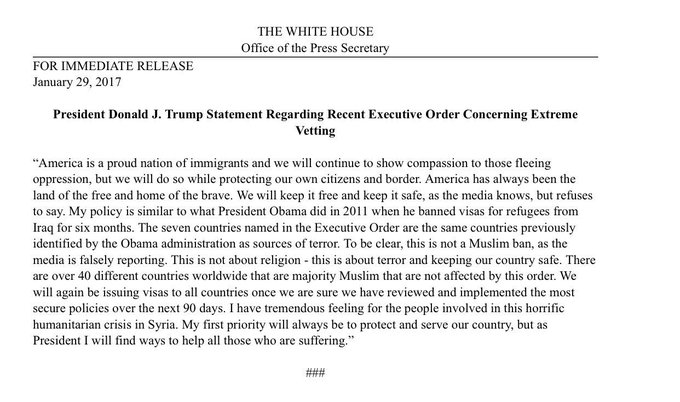

Their arrests in 2011 prompted then President Barack Obama to slow the Iraqi refugee program in the United States for several months. The government tightened the vetting process, including checking refugee fingerprints against IEDs.

A 2013 ABC News investigation into the case reported that a pattern was suspected: “Several dozen suspected terrorist bombmakers, including some believed to have targeted American troops, may have mistakenly been allowed to move to the United States as war refugees, according to FBI agents investigating the remnants of roadside bombs recovered from Iraq and Afghanistan.” That figure included the two men. The sentencing memo says that, before becoming a refugee to America, Alwan “stated that he left Iraq and fled to Syria because he was wanted in Iraq for insurgent activities.” Several years before being allowed into the United States, he was arrested “in Iraq for IED activity.”

“These two former Iraqi insurgents participated in terrorist activities overseas and attempted to continue providing material support to terrorists while they lived here in the United States,” the assistant attorney general prosecuting the case said when the men were sentenced in 2011.

Both President Donald Trump and Conway have jumped on the Bowling Green case to accuse the media and critics of a double standard in analyzing Trump’s immigration ban. However, Trump’s ban encompasses seven countries (including Iraq), including one indefinite ban (Syria), and it applies to nationals from those countries, not just refugees. Initially, the Trump ban also roped in green card holders, although the administration later clarified that green card holders were exempt.

Here’s what you need to know:

1. The Men Were Convicted of Trying to Help Al-Qaeda Harm U.S. Soldiers, Whom Alwan Referred to as ‘Lunch and Dinner’

Both men were Iraqi citizens who were living in Bowling Green, Ky. at the time of their arrests.

They “admitted using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) against U.S. soldiers in Iraq and…attempted to send weapons and money to Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) for the purpose of killing U.S. soldiers,” the Department of Justice press release announcing the men’s sentencing said.

Hammadi pleaded guilty on Aug. 21, 2012, to 12 counts; he was accused of “attempting to provide material support to terrorists and to AQI; conspiring to transfer, possess and export Stinger missiles; and making a false statement in an immigration application,” said DOJ. His case is still open because he is now challenging his sentence, according to federal court records.

DOJ said Alwan “pleaded guilty to conspiring to kill U.S. nationals abroad; conspiring to use a weapon of mass destruction (explosives) against U.S. nationals abroad; distributing information on the manufacture and use of IEDs; attempting to provide material support to terrorists and to AQI and conspiring to transfer, possess and export Stinger missiles.”

You can read the government’s sentencing memorandum for Alwan here:

The men thought they were moving very valuable equipment, but their activities were being videotaped by authorities. “They loaded five rocket-propelled grenade launchers, five machine guns, five cases of C4 explosive, two sniper rifles, one box of 12 hand grenades, two Stinger surface-to-air missile launchers and what they believed to be a total of $565,000,” the release said.

Alwan “spoke of his efforts to kill U.S. soldiers in Iraq, stating ‘lunch and dinner would be an American,'” the release says.

According to the release, Hammadi was sentenced to life in federal prison, and Alwan was sentenced to 40 years in federal prison, followed by a life term of supervised release. Both defendants had pleaded guilty to federal terrorism charges.

“These are experienced terrorists who willingly and enthusiastically participated in what they believed were insurgent support operations designed to harm American soldiers in Iraq,” the U.S. attorney said in the release, which adds that Alwan received a lesser sentence because he cooperated with the prosecution.

2. Conway Was Mocked for Referring to the Plot as a ‘Massacre’

Donald Trump’s adviser Kellyanne Conway was criticized on social media for referring to Bowling Green as a massacre. The men in question aimed to harm American soldiers overseas. Trump critics quickly leapt to criticize Conway, although the Bowling Green case was certainly very serious. That didn’t stop Twitter from laughing:

Here’s what Conway said to MSNBC’s Chris Matthews:

I bet it’s brand new information to people that President Obama had a six-month ban on the Iraqi refugee program after two Iraqis came here to this country, were radicalized and they were the masterminds behind the Bowling Green massacre. Most people don’t know that because it didn’t get covered.

The local newspaper – the Bowling Green Daily News – noted that the case received extensive coverage.

National news outlets also did major exposes on the Bowling Green plot at the time.

3. Both Men Admitted to Trying to Harm U.S. Soldiers in Iraq & Hammadi Participated in a Dozen Attacks

Alwan “admitted participating in IED attacks against U.S. soldiers in Iraq, and Hammadi admitted to participating in 10 to 11 IED attacks as well as shooting at a U.S. soldier in an observation tower,” the release said.

The men’s activities were foiled when the feds used a confidential informant to infiltrate their circle.

The confidential informant told Alwan “that he was working with a group to ship money and weapons to Mujahadeen in Iraq. From September 2010 through May 2011, Alwan participated in ten separate operations to send weapons and money that he believed were destined for terrorists in Iraq,” the DOJ said.

Between October 2010 and January 2011, “Alwan drew diagrams of multiple types of IEDs” and showed the informant how to make them. In January 2011, “Alwan recruited Hammadi, a fellow Iraqi national living in Bowling Green, to assist in these material support operations,” according to the release.

“Beginning in January 2011 and continuing until his arrest in late May 2011, Hammadi participated with Alwan in helping load money and weapons that he believed were destined for terrorists in Iraq,” the release says.

4. Alwan’s Fingerprints Were Found on an Unexploded IED in Iraq

In recorded conversations with the confidential informant, “Alwan allegedly stated that he used to procure explosives and missiles while an insurgent in Iraq; that his insurgent group conducted strikes daily; and that he used IEDs in Iraq hundreds of times,” another DOJ press release says, this one announcing the men’s indictment.

“At one point, Alwan allegedly drew diagrams of four types of IEDs for the CHS and provided verbal instructions on how to build these devices. He also discussed occasions in which he had used these types of IEDs against U.S. troops. Asked whether he had achieved results from these devices in Iraq, Alwan allegedly replied, ‘Oh yes,’ mentioning that his attacks had ‘f–ked up’ Hummers and also targeted Bradley fighting vehicles,” the release said.

The release, which summarizes the charging documents, says the FBI identified two latent fingerprints belonging to Alwan “on a component of an unexploded IED that was recovered by U.S. forces near Bayji, Iraq. Alwan had allegedly advised the (informant) that he lived in that area of Iraq and worked at the power plant in Bayji. Alwan had also allegedly told the (informant) how he had used a particular brand of cordless telephone base station in IEDs. Alwan’s fingerprints were allegedly found on this particular brand of cordless base station in the IED that was recovered in Iraq.”

The sentencing memo says that Alwan said his group in Iraq “had planned to detonate the IED against a United States military convoy the following morning but it was discovered and removed before they returned to detonate the device.”

Furthermore, Alwan, the charging documents said, “also described IED attacks on U.S. troops that he participated in with others, including an associate whom Alwan said had lost an eye when an IED exploded prematurely. According to the charging documents, U.S. forces recovered an unexploded IED near Bayji from which a latent fingerprint belonging to this associate was later recovered. The charging documents allege that this associate was detained by U.S. troops in June 2006 and had a false eye.”

5. The Men Came to the United States as Refugees & the Case Led Obama to Tighten Vetting for the Iraqi Refugee Program to the U.S.

Obama during his final press conference as President. (Getty)

The case of the two Iraqis “did raise questions about the government’s process for clearing refugees for migration to the U.S.,” CBS News reported in 2015, adding that it led to an increase in government vetting procedures.

The Mirror describes what Obama did this way: “Paused approvals of refugee applications from Iraq for a period of six months after two Iraqi al-Qaeda terrorists were discovered living as refugees in Kentucky.” The news site says Obama’s action was in response to a “specific event” and designed to give authorities time to do the fingerprint matches off recovered IEDs. ABC news had reported in 2013 that the president temporarily “stopped” processing Iraqi refugees while the program was tightened.

However, The Washington Post reported that a former Obama administration official named on Finer has “denied that any ban in Iraqi refugee admissions was put in place under Obama.”

“While the flow of Iraqi refugees slowed significantly during the Obama administration’s review, refugees continued to be admitted to the United States during that time, and there was not a single month in which no Iraqis arrived here,” Finer wrote in Foreign Policy, according to The Post. “In other words, while there were delays in processing, there was no outright ban.” (Another official backed up Finer’s account to the Post.)

The Post did reprint this 2011 exchange between Republican Senator from Maine, Susan Collins, and then Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano as to whether “a hold had been placed on Iraqi visa applications.” Collins asked at the congressional hearing: “So my question is, is there a hold on that population until they can be more stringently vetted to ensure that we’re not letting into this country, people who would do us harm?” Napolitano responded,

Yep. Let me, if I might, answer your question two parts. First part, with respect to the 56, 57,000 who were resettled pursuant to the original resettlement program, they have all been revetted against all of the DHS databases, all of the NCTC [National Counter Terrorism Center] databases and the Department of Defense’s biometric databases and so that work has now been done and focused.

On March 1, 2009, two years before the controversy, Hammadi, seeking refugee status, signed a form entitled “Sworn Statement of Refugee Applying for Admission to the United States” (Refugee Application), according to the sentencing memorandum in his case. He checked no in boxes that asked questions about terrorist activity. Refugee status was granted, and he arrived in the U.S.

You can read the memo here:

In fact, the memo says, Hammadi “was associated with the Jaysh al Mujahidin terrorist group in Iraq. Hammadi was taught how to build and use IEDs in Iraq. Hammadi told of his first attack on U.S. forces in Iraq in 2006 and stated it was on a main highway in Iraq and the IED was placed on the side of the road and covered with sand. Hammadi stated that the IED was detonated by a remote device and that Hammadi and his associates targeted a Humvee and multiple trucks.”

Trump brought up Obama’s pausing refugee admittance from Iraq for six months after his immigration ban received criticism, although there are many differences between his ban and the more limited action that Obama took.

According to CBS, the two men were Iraqi refugees. A U.S. government sentencing memorandum in Alwan’s case reads, “The Bowling Green office of the FBI’s Louisville Division initiated an investigation of Waad Ramadan Alwan in or about 2009. Alwan is an Iraqi national living in Bowling Green, Kentucky. He entered the United States on or about April 22, 2009, under a United States refugee program.”

You can read a defense memo in Hammadi’s case here:

Federal officials “already had evidence of Alwan’s ties to the Iraq insurgency from a fingerprint on a roadside bomb found in 2005, but it didn’t stop him from entering the U.S. as a refugee four years later. Federal investigators starting tracking Alwan after discovering he had been held in an Iraqi prison,” CBS News reported.