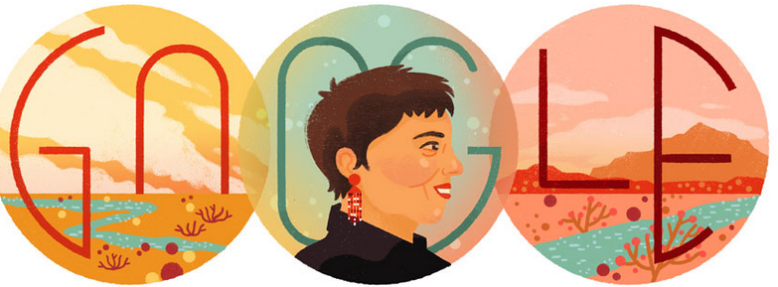

Google Gloria E. Anzaldúa Google Doodle.

Gloria E. Anzaldúa, an influential cultural theorist and author who transformed dividing lines “into unifying visions,” is the subject of the September 26 Google Doodle in honor of her 75th birthday.

“For writer and scholar Gloria E. Anzaldúa, a border wasn’t just a line on a map: it was a state of mind and a viewpoint on life. Born on this date in 1942 in the Rio Grande Valley, Anzaldúa possessed an astounding gift for transforming dividing lines into unifying visions,” Google noted.

Anzaldúa’s writing came from her own experiences and multiple identities. She saw living across borders as “geographical, social… philosophical,” according to Google.

“Whether writing poetry, fiction, autobiography, or theory, Gloria Anzaldúa drew on and fictionalized her personal experiences to explore diverse political, spiritual, and aesthetic issues. Her redefinition of Chicana/o identities, use of code-switching, and innovative borderlands theories have influenced many fields, including American studies, composition studies, cultural studies, ethnic studies, feminism and feminist theory, literary studies, queer theory, and women’s studies,” according to the American National Biography Online.

Here’s what you need to know:

1. Anzaldúa, Who Was Born in Texas, Experienced Segregated Schools but Wrote to Capture the ‘Magic of the Landscape Around Her’

Anzaldúa was born in 1942 and died in 2004. Regarded as an “author, cultural theorist, and feminist philosopher,” she was born in Raymondville, Texas, “the oldest of four children of Urbano and Amalia (García) Anzaldúa, sixth-generation Mexican-American rancher-farmers,” the American National Biography reports.

“Growing up on ranches and farms in Texas-Mexico border towns, Anzaldúa developed a profound appreciation for the earth and its riches. She fell in love with art and writing as a way to capture the magic of the landscape around her,” Google reports. “She also faced racism and isolation, but that didn’t stop her from becoming a stellar scholar.”

Health issues in childhood gave her deep empathy for others.

“Gloria was diagnosed in infancy with a rare hormonal disorder that triggered premature puberty, including monthly menses from the age of six. This hormonal condition marked Gloria as physiologically different from her peers, fostering in her a lifelong empathy for other outsiders, which motivated her social justice work and her desire to use the written word to create new forms of inclusionary communities,” the biography notes.

“Gloria’s sense of difference was heightened when she entered Texas’s segregated educational system in 1949. Because she spoke only Spanish, her teacher mocked and punished her. Despite this ostracism, Gloria excelled in school.”

2. Anzaldúa Has Influenced Generations & Encouraged People to Embrace Living in Multiple Worlds, Calling Life ‘This Place of Contradictions’

In a 2016 tribute on her 74th birthday, Latina.com described how Anzaldúa influenced many Latinas with her writings and quest for social justice.

“Her work as a theorist, writer and activist continues to impact generations of Latinas living on the borderlands, both geo-politically and metaphorically,” the site notes.

“Anzaldúa taught us that we are multidimensional, in a constant state of becoming, and, despite dominant culture’s obsession with placing people in fixed, binary boxes, our plurality, and its intersections, makes us whole and gives us la facultad, a perspective and power that’s all our own.”

Google described how Anzaldúa “realized early on that she lived in many worlds at once: she was both American and Mexican, both native and foreigner.”

“It’s not a comfortable territory to live in, this place of contradictions,” Anzaldúa noted. “She understood that the way forward was not to choose a side, but to embrace a third place — a land of both, not either/or,” Google wrote.

“Anzaldúa mapped this new frontier with her pen. Her most famous work, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, alternates between English and Spanish and includes a variety of forms — from poem to prose, from critique to confessional. This striking mix of voices and perspectives earned Borderlands a place on Literary Journal’s list of best books of 1987.”

The Latina.com article contains a compilation of writings from women influenced by Anzaldúa’s work. For example, Barbara A. Sostaita, of Durham, North Carolina, wrote in part, “I discovered Anzaldúa’s work when I was a junior in college. At the time, I was struggling to come to terms with my place in the world and in the academy. Was I too brown to survive in such a white-dominated world? Was I too mestiza, too much of a crossbreed, to fit inside disciplinary borders and boxes?…Anzaldúa taught me that living in multiple worlds is not an impairment but a possibility.”

3. Anzaldúa Was Known for Her Book ‘Borderlands/La Frontera’

The book ‘Borderlands/La Frontera’ is how many people know Gloria Anzaldúa. That’s not all she wrote, though. Far from it. According to a Foundation in her name, “She is most famous for her work co-editing the anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women of Color. Anzaldua also wrote various children’s books and poetic works. However, her main focus was the border created by language and even writes in a bilingual manner in order to highlight the distinct troubles with language. By using the two variations of English and the six different variations of Spanish in Borderlands/ La Frontera, Anzaldua puts the reader right in her mind and exposes the way she thinks.”

The introduction to the book on Amazon says that it drew on her “experience as a Chicana, a lesbian, an activist, and a writer,” and adds, “the essays and poems in this volume profoundly challenged, and continue to challenge, how we think about identity. BORDERLANDS/LA FRONTERA remaps our understanding of what a ‘border’ is, presenting it not as a simple divide between here and there, us and them, but as a psychic, social, and cultural terrain that we inhabit, and that inhabits all of us.”

“The emotional and intellectual impact of the book is disorienting and powerful…all languages are spoken, and survival depends on understanding all modes of thought. In the borderlands new creatures come into being. Anzaldúa celebrates this ‘new mestiza’ in bold, experimental writing,” The Village Voice wrote in a review excerpted on the Amazon page.

“Anzaldúa’s pulsating weaving of innovative poetry with sparse informative prose brings us deep into the insider/outsider consciousness of the borderlands; that ancient and contemporary, crashing and blending world that divides and unites America,” wrote Women’s Review of Books in another.

An excerpt from the book reads,

To live in the Borderlands means you

are neither hispana india negra espanola ni gabacha, eres mestiza, mulata, half-breed caught in the crossfire between camps while carrying all five races on your back not knowing which side to turn to, run from;

To live in the Borderlands means knowing that the india in you, betrayed for 500 years, is no longer speaking to you, that mexicanas call you rajetas, that denying the Anglo inside you is as bad as having denied the Indian or Black;

Cuando vives en la frontera

people walk through you, the wind steals your voice, you’re a burra, buey, scapegoat, forerunner of a new race, half and half-both woman and man, neithera new gender;

To live in the Borderlands means to put chile in the borscht, eat whole wheat tortillas, speak Tex-Mex with a Brooklyn accent; be stopped by la migra at the border checkpoints;

Living in the Borderlands means you fight hard to resist the gold elixir beckoning from the bottle, the pull of the gun barrel, the rope crushing the hollow of your throat…

The foundation adds, “Borderlands/La Frontera is dedicated to being proud of one’s self, heritage, and the recognition of all cultures.” You can read more excerpts from the book here.

4. Anzaldúa Worked as a Migrant Farmer & in a Bilingual Preschool & Became Highly Educated

Growing up, Anzaldúa spent time as a migrant farmer alongside her parents and siblings, according to a biography of her.

“Realizing this lifestyle would not benefit his children’s education, Anzaldúa’s father decided to keep his family in Hargill, where he died when Anzaldúa was 14. His death meant that Anzaldúa was obligated financially to continue working the family fields throughout high school and college, while also making time for her reading, writing, and drawing,” the biography reports.

According to a foundation in her name, “Growing up her family moved to various ranches working as migrant farmers. Anzaldua gained all of her knowledge about the Southern Texas and Chicano discrimination while working on the farm and ranches to help with expenses.”

She went on to receive a B.A. in English, Art, and Secondary Education and an M.A. in English and Education. “She first taught in a bilingual preschool program, then in a Special Education program for mentally and emotionally handicapped students,” the biography noted, adding that she later taught in a university setting on topics including ” Feminism, Chicano Studies, and Creative Writing.”

5. Anzaldúa Died of Complications From Diabetes but Her Words Live On

Tragically, Anzaldúa was taken from the world too soon, dying from complications of Diabetes, according to the foundation. However, she left behind her thoughts and values in words. Many people have shared her quotes online, in addition to reading her books. “Writing is dangerous because we are afraid of what the writing reveals …And a woman with power is feared,” is one quote often shared.

“She taught preschool and special education before moving to California in 1977,” the foundation notes. “While in California she supported herself through her writing, lectures and teachings about feminism, Chicano studies, and discrimination. In 1974, Anzaldua moved back to Texas to continue her graduate and doctoral studies at the University of Texas at Austin. While at UTA, she taught a course called ‘La Mujer Chicana’ and this is where she began to notice the lack of material written for or about Chicana women.”

“Her theories had impact across disciplines, including Chicano/a Studies, Women’s Studies, LGBT Studies, and Postcolonial Studies. She was awarded a posthumous Ph.D. in literature by the University of California Santa Cruz,” Google noted.