Antoni van Leeuwenhoeks is being celebrated with a Google Doodle on what would have been his 384th birthday. (Google)

Dutch scientist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek is being celebrated on what would have been his 384th birthday with a Google Doodle.

“Considered the first microbiologist, van Leeuwenhoek designed single-lens microscopes to unlock the mysteries of everything from bits of cheese to complex insect eyes,” Google says. “In a letter to the Royal Society of London, van Leeuwenhoek marveled at what he had seen in a sample of water from a nearby lake: ‘little animals’ that we know now as bacteria and other microbes.”

Doodler Gerben Steenks said, “I chose to make it an animated Doodle to show the ‘before and after’ experience that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek had — looking through a microscope and seeing a surprising new world.”

Here’s what you need to know about van Leeuwenhoek:

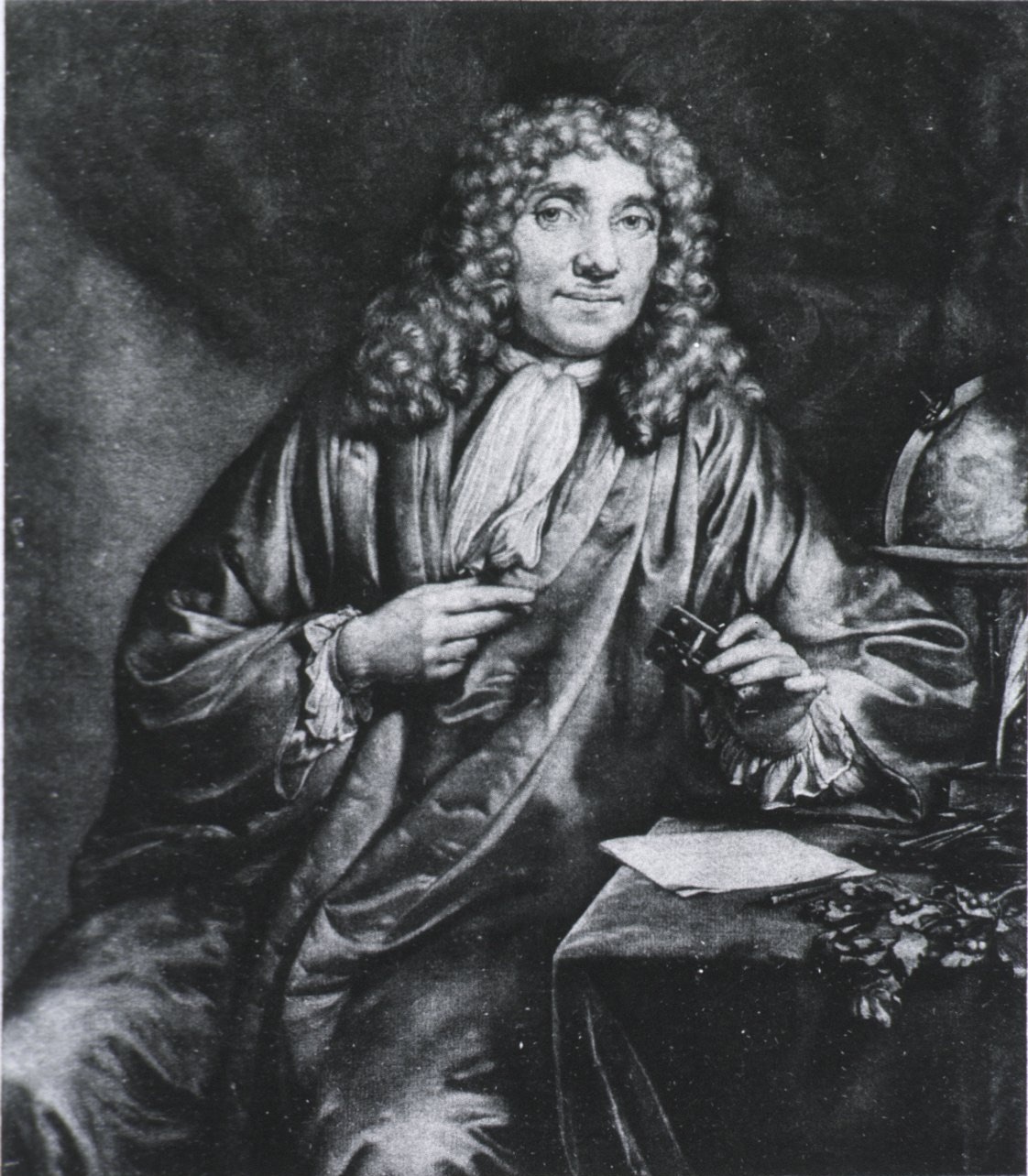

1. He Was Born in the Dutch Republic City of Delft in 1632 & Lived Most of His Life There

(Wikimedia Commons)

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek was born October 24, 1632 in the Dutch Republic city of Delft, according to vanleeuwenhoek.com, a website dedicated to his legacy.

He was born as Thonis Philipszoon, but preferred to be called Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, which means “Anthony from the Lion’s Corner,” taken from the “location of his father’s corner house near the Leeuwenpoort, the ‘Lion’s Port’ in Delft’s East End.”

His father was a basket maker who died when he was 5 and his mother was from the family of a local brewer. His only formal education came briefly in Warmond, before he returned home to Delft and became a bookkeeper’s apprentice for a draper.

He lived most of his life in Delft, opening his own woolen shop and also held several lucrative political jobs in the municipal government.

“…van Leeuwenhoek was an unlikely scientist. A tradesman of Delft, Holland, he came from a family of tradesmen, had no fortune, received no higher education or university degrees, and knew no languages other than his native Dutch,” the University of California-Berkeley wrote on its website about historical figures in science. “This would have been enough to exclude him from the scientific community of his time completely. Yet with skill, diligence, an endless curiosity, and an open mind free of the scientific dogma of his day, Leeuwenhoek succeeded in making some of the most important discoveries in the history of biology.”

2. He Handcrafted the Lenses for His Microscopes & Had His Groundbreaking Work Published by the Royal Society

Van Leeuwenhoek handcrafted the lenses for his micropscopes. He made over 500, according to the University of California-Berkeley’s biography of him:

In basic design, probably all of Leeuwenhoek’s instruments — certainly all the ones that are known — were simply powerful magnifying glasses, not compound microscopes of the type used today. A drawing of one of Leeuwenhoek’s “microscopes” is shown at the left. Compared to modern microscopes, it is an extremely simple device, using only one lens, mounted in a tiny hole in the brass plate that makes up the body of the instrument. The specimen was mounted on the sharp point that sticks up in front of the lens, and its position and focus could be adjusted by turning the two screws. The entire instrument was only 3-4 inches long, and had to be held up close to the eye; it required good lighting and great patience to use.

Compound microscopes (that is, microscopes using more than one lens) had been invented around 1595, nearly forty years before Leeuwenhoek was born. Several of Leeuwenhoek’s predecessors and contemporaries, notably Robert Hooke in England and Jan Swammerdam in the Netherlands, had built compound microscopes and were making important discoveries with them. These were much more similar to the microscopes in use today. Thus, although Leeuwenhoek is sometimes called “the inventor of the microscope,” he was no such thing.

However, because of various technical difficulties in building them, early compound microscopes were not practical for magnifying objects more than about twenty or thirty times natural size. Leeuwenhoek’s skill at grinding lenses, together with his naturally acute eyesight and great care in adjusting the lighting where he worked, enabled him to build microscopes that magnified over 200 times, with clearer and brighter images than any of his colleagues could achieve. What further distinguished him was his curiosity to observe almost anything that could be placed under his lenses, and his care in describing what he saw. Although he himself could not draw well, he hired an illustrator to prepare drawings of the things he saw, to accompany his written descriptions. Most of his descriptions of microorganisms are instantly recognizable.

Van Leeuwenhoek was also notable because he never published his own formal study. His discoveries were publicized through letters to the noted Royal Society in London, according to the BBC.

“In 1673, he reported his first observations – bee mouthparts and stings, a human louse and a fungus – to the Royal Society. He was elected a member of the society in 1680 and continued his association for the rest of his life by correspondence,” according to the BBC.

3. He Made Several Notable Discoveries During His Scientific Career Along With Bacteria

He made several important discoveries during his scientific career, along with his most notable discovery of bacteria, according to FamousScientists.org.

His first discovery came in 1674, at the age of 41, when he found single-celled life forms in water.’

“Nowadays these organisms are grouped with the protists – these are mainly single-celled plants and animals. Echoing the initial disbelief Hooke’s Micrographia had met, many members of the Royal Society refused to believe in the existence of Leeuwenhoek’s microscopic creatures,” according to Famous Scientists. “It took until 1677 before their existence was fully accepted. This happened after Robert Hooke returned to his microscopes, which he had given up because of eye strain, and verified Leeuwenhoek’s observations.”

His discovery of bacteria, including motile bacillus, selenomonads and a micrococcus, came in 1683, while he was examining dental tartar.

According to vanleeuwenhoek.com, he made several other discoveries.

In 1674, he found that yeast consists of invidiual plant-like organisms. In 1677, he was the first to discover spermatozoa in humans, dogs, swine, mollusks, amphibians, fish and birds, “He often opined that this was his greatest find. At least at first, he thought that they were parasites in the male genitalia. The role of bulk semen in reproduction was already recognized.” In 1683, he observed bacteria in feces.

He also discovered, “the lymphatic capillaries, which contained ‘a white fluid, like milk,’ that same year, according to Famous Scientists, which describes some of his other scientific finds:

By observing the life-cycles of maggots and fleas Leeuwenhoek proved that such creatures are not spontaneously generated, as many people believed at the time. He showed these creatures go through a process of reproduction from eggs to maggots to pupae to adults.

By dissecting aphids he discovered parthenogenesis. He found parent aphids containing the embryos of new aphids although eggs had not been fertilized.

By observing the flow of blood in tiny capillaries, Leeuwenhoek confirmed William Harvey’s work on blood circulation.

4. He Was Married Twice & Had a Daughter, Along With 4 Other Children Who Died in Infancy

(Wikimedia Commons)

Van Leeuwenhoek was married twice, first to Barbara de May, in 1654, according to Famous Scientists.

They had five children together, but only their daughter, Maria, survived past infancy.

He remarried, to Cornelia Swalmius, in 1671, five years after his first wife died. They had no children and were together until Swalmius died in 1694.

5. He Died of 1723 of a Rare Disease — Which Is Now Named for Him — That Caused the ‘Uncontrolled Movement of the Midriff’

Van Leeuwenhoek died on August 26, 1723, at the age of 90. He continued writing to the Royal Society and other scientific organizations until he was near death, including letters about the rare illness he was battling, according to FamousScientists.org.

The disease, which caused the “uncontrolled movement of the midriff,” is now named Van Leeuwenhoek’s Disease for him, according to the website. The disease causes uncontrollable muscle twitches.