Wikimedia Commons / The Library of Congress Wilder Penfield

Google is honoring Wilder Penfield’s 127th birthday with a Google Doodle today, January 26. Penfield was born on January 26, 1891, and died on April 5, 1976 from abdominal cancer at the age of 85. He was once called “The Greatest Living Canadian” for his breakthroughs in brain surgery and his unmatched achievements in mapping the brain. He was Montreal’s first neurosurgeon and in 1934 established the Montreal Neurological Institute. He made great strides in treating epilepsy and improved many, many lives with his work — which just happened to be his life’s goal. But even with all his success, he couldn’t save his own sister from brain cancer, although a radical surgery that he performed did give her a couple extra years of life. He studied medicine because he believed it was “the best way to make the world a better place.” He had four children who inherited his love of helping others, including one who created a children’s center herself.

1. Penfield’s Father Abandoned Him, But His Mother Was His Biggest Supporter

Penfield was born in Spokane, Washington. His father, Charles Samuel Penfield, was an unsuccessful physician who struggled with finances. Charles abandoned Penfield’s family when Penfield was just eight. Penfield’s mom, Jean Jefferson Penfield, moved Penfield and his brother and sister to Hudson, Wisconsin in 1899 and they lived with his grandfather for a time. Jean founded the Galahad School for Boys, where Penfield attended high school. It was Jean who first alerted Penfield to the Rhodes Scholarship, which he later won. “This is just the thing for you,” he said she told him.

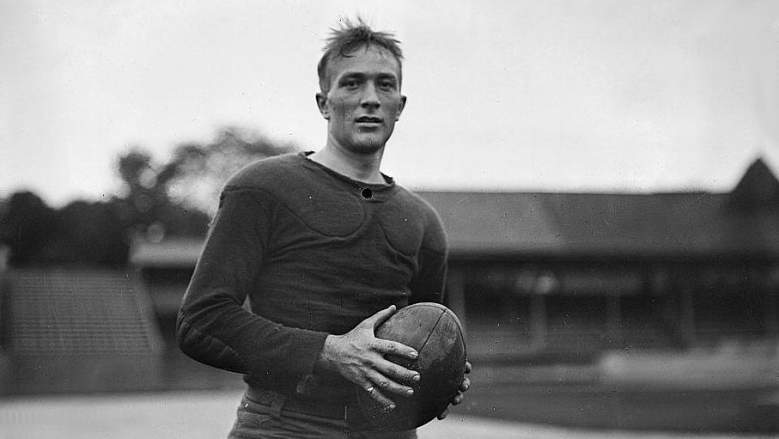

He studied at Princeton, where he was a member of the Cap and Gown, and played football. He studied neuropathology at Merton College in Oxford, and then served as a dresser at a military hospital in Paris. He had a wide and varied career, working in many locations before performing his very first solo epilepsy operation at the Neurological Institute of New York. He became Montreal’s first neurosurgeon after an opportunity to study epilepsy under an endowment from David Rockefeller fell through. (Penfield wasn’t the type to give up when one door closed. He was always looking for the next door to open.) In 1934, he became a Canadian citizen after he and Dr. William Cone founded the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, with funding from Rockefeller.

2. He and His Wife, Helen, Had Four Talented Children, Including a Daughter Who Started a Center for Disabled Children

In 1917 he married Helen Kermott. He met her at the age of 16, his biography explains, when he was invited to parties and boat-trips during the summer. He liked her right away, but was worried because two of his other friends like her too. “She is the only one I would care much about,” he wrote in his diary. He and Helen stayed close, even after he went to college, when they wrote letters. He once wrote her: “My studying is done but there is no time to answer your letter or thank you for the pictures. The moon is full and I feel as though I must talk to you a little while… Do you still wish on the evening star?” Later, he felt appalled at the idea of not marrying her for many years, and having to go through all his studies to be a doctor first. But he felt it wasn’t right to propose until he could support her. In 1914, she told him that she was briefly engaged to another man, William Webster, but after spending time with Wilder she realized she couldn’t marry William. But she still had many other offers. That’s when Wilder finally told her that he had been in love with her for five years. The next day, he proposed to her.

They had four children: Wilder Graves Penfield Jr., Ruth Mary Penfield Lewis (married to Crosby Lewis), Priscilla Penfield Chester, and Dr. Amos Jefferson Penfield.

Their daughter, Priscilla Penfield Chester, worked actively to help disabled children. After one of her friend’s children suffered a brain injury from a near drowning, Priscilla created the Penfield Children’s Center in Wisconsin. She asked her dad for advice after her friend’s child was injured, and he mentioned Maria Montessori’s work and a school she had opened in Rome. Priscilla visited the school in Rome, and it eventually led to the creation of the Penfield Children’s Center. In 2014, the Center was serving 1,700 children a year.

Priscilla died February 19, 2014, in Vermont after a stroke at the age of 88. Priscilla and her husband, Bill, met because their fathers were roommates at Princeton. She left behind three daughters, 10 grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

Wilder Penfield’s grandson, Howard Jefferson Lewis (son of his daughter Ruth), wrote Penfield’s biography: Something Hidden. The biography was later turned into a movie. Howard Lewis and his wife, Catherine, had a daughter, Cleo Lewis.

Wilder’s oldest son, Wilder Penfield Jr., died in 1988 of leukemia. From 1941 to 1945, Wilder Jr. served as captain of the Canadian Intelligence Corps. He was later an export manager and then director of vocational development at Dawson College. He and his wife, Berry, had a daughter, Wendy, and a son, Wilder Penfield III. Wilder III was a well-known journalist with the Toronto Sun who wrote about music and culture.

Amos “Jeff” Jefferson Penfield died in 2011 of a malignant melanoma, leaving behind his wife Katharine and two daughters, a son, and seven grandchildren. Jeff served in the Korean War in the medical corps and practiced Ob/Gyn for more than 30 years.

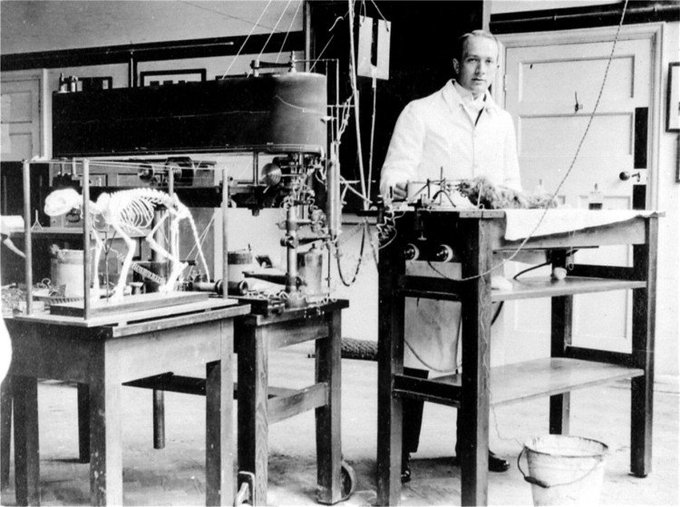

3. Penfield Pioneered the Idea of Mapping the Brain While His Patients Were Conscious

Many seizures begin with abnormal activity in a small part of the brain, disrupting motor and cognitive functions, and the abnormal activity then spreads to other parts of the brain. Penfield and Herbert Jasper invented the Montreal Procedure for severe epilepsy. The procedure destroys nerve cells in the brain where seizures originate. The surgeon peels back part of the skull and uses electrodes to stimulate the brain while the person is conscious, to accurately target the areas responsible for epilepsy and reduce side effects. The surgeon maps the responses in different parts of the brain, noting which causes responses that mimi auras or other motor activities that happen at the start of a seizure. The brain tissue responsible is destroyed. But the surgeon also notes while mapping the brain which parts are vital, such as when parts of the brain are stimulated and the patient loses the ability to recall words. Those vital areas are mapped and spared.

His techniques for the Montreal Procedure also let him map the brain’s sensory and motor cortices and show their connections throughout the body. He was so ahead of his time and so accurate that those maps are still used today, and are nearly unaltered. His work helped people understand the localization of brain function, along with seeing how regions overlap. Interestingly, this overlap can vary from individual to individual. He created a cortical homunculus map, showing how the brain sees the body. His first diagram was published in 1937 and a revised version was published in 1950.

4. Penfield Discovered that Stimulating the Temporal Lobe Can Cause Vivid Memory Recall

It was Penfield who discovered that stimulating temporal lobes can create vivid recall of memories. The Google Doodle for today demonstrates this, by showing a stimulated brain recalling the smell of burned toast. For example, one patient saw a 7-Up bottling company and a bakery from years in the past. Another heard a theme song from an old radio show. A boy heard his mom telling him that his coat was on wrong and then he heard his mom talking on the phone to his aunt. Oliver Sacks, in his book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, described Penfield’s discovery this way: “Such stimulations would instantly call forth intensely vivid hallucinations of tunes, people, scenes, which would be experienced, lived, as compellingly real, in spite of the prosaic atmosphere of the operating room, and could be described to those present in fascinating detail…” Sacks went on to talk about two of his patients and then said: “Such epileptic hallucinations or dreams, Penfield showed, are never phantasies; they are always memories, and memories of the most precise and vivid kind, accompanied by the emotions which accompanied the original experience. Their extraordinary and consistent detail, which was evoked each time the cortex was stimulated, and exceeded anything which could be recalled by ordinary memory, suggested to Penfield that the brain retained an almost perfect record of every lifetime’s experience.”

Penfield also noted that some of his patients, when their temporal lobes were stimulated, could not only recall dreams, but had hallucinations and out-of-body experiences. (It was this discovery that served as the inspiration for Philip K. Dick’s “Mood Organ” in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, a device that can change a person’s mood by dialing the mood on a number pad.) Some also experienced feelings of strangeness, loneliness, and deja vu.

5. Penfield Performed a Radical Surgery on His Sister, Trying to Save Her from a Brain Tumor

Penfield’s older sister, Ruth, had severe epileptic seizures. She had severe headaches from the age of 14 and had a Jacksonian seizure when she was 20. Her cortex was then quiet for the next eight years, but then she started suffering more and more seizures as she neared her 40s. It was soon apparent that she was suffering some type of glioma: a brain tumor that invades essential structures within the brain itself. In an attempt to save her, MindHacks reported, Penfield removed almost her entire right frontal lobe. This surgery, as with his others, involved checking her reactions while she was awake to make sure parts that served vital functions weren’t removed. During her operation, Ruth seemed most worried about embarrassing her brother on the job. Penfield’s colleague, Colin Russel, said: “She said that she had felt so afraid of causing you distress by making an exhibition of herself… When I remarked that the only exhibition I had seen was one of the best exhibitions of courage that it had been my fortune to witness, she expressed her gratitude so nicely that one could not help wondering how much of the frontal lobe had to do with higher association processes.”

Ruth returned to her regular life as a wife and mom of six after the surgery. Her good humor and eloquence stayed, but she had troubled with planning and organization. Two years later, her symptoms returned. It turned out that her tumor had regrown. Penfield’s mentor, Harvey Cushing, removed the tumor again. But Ruth only survived another few months before dying. Penfield couldn’t save his sister, but he gave her two more years of life. After much struggling, Penfield published an article in 1935 about three cases, including his sister’s. He believed that is what she would have wanted.

As with everything in life, Penfield learned, even from his losses, and used that loss to help others. He developed the Penfield dissector, which is a less-injurious method in brain surgery and still is used today. Penfield was also an author and championed university education and bilingualism. He was given the Lister Medal for surgical science.