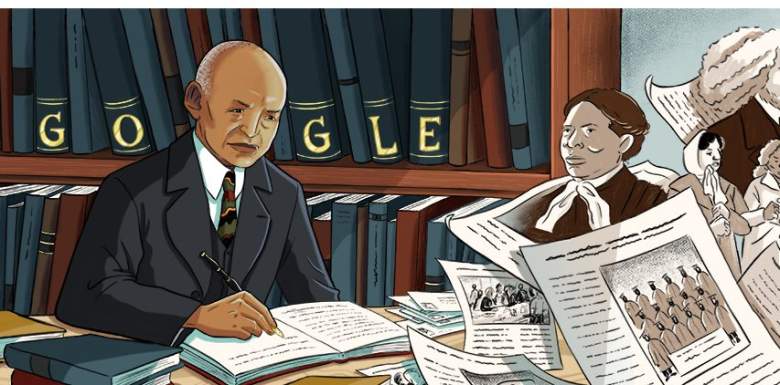

Carter G. Woodson, an author, educator, and historian who is often dubbed the “Father of Black History,” is being honored with a Google Doodle on the first day of Black History Month.

Woodson was a man who loved education, who excelled at it, and who was dedicated to highlighting and preserving the importance and richness of black history. Dr. Woodson died in 1950, but his profound legacy lives on every February and in a greater understanding about the contributions and struggles of African-Americans.

“Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history,” Woodson once said in one of his most-recognized quotes. He emphasized African-American “self-empowerment” while writing on the “Western indoctrination system,” according to Biography.com.

Explaining the importance of Woodson, the NAACP notes, “Carter G. Woodson believed that Blacks should know their past in order to participate intelligently in the affairs in our country. He strongly believed that Black history – which others have tried so diligently to erase – is a firm foundation for young Black Americans to build on in order to become productive citizens of our society.”

Here’s what you need to know:

1. Carter G. Woodson Was Born to Former Slaves & Learned Important Values From His Father

Woodson’s parents were former slaves. He was born in 1875 in New Canton, Virginia, to Anne Eliza and James Henry Woodson, according to Google. Growing up, Woodson held many different jobs. “During the 1890s, he hired himself out as a farm and manual laborer, drove a garbage truck, worked in coalmines, and attended high school and college in Berea College, Kentucky—from which he earned a B.L. degree in 1903,” notes Blackpast.org.

The biography that accompanies Woodson’s Google Doodle notes that, despite Woodson’s parents’ lack of opportunity, or maybe because of it, he developed “an appetite for education from the very beginning.”

First, though, he had to toil hard to support his family. “As a young man, he helped support his family through farming and working as a miner, which meant that most of his education came via self-instruction. He eventually entered high school at the age of 20 and earned his diploma in less than two years,” wrote Sherice Torres, Director of Brand Marketing at Google & Black Googlers Network member.

According to the NAACP, Woodson credited his father for forming his values, once writing that his father taught him that “learning to accept insult, to compromise on principle, to mislead your fellow man, or to betray your people, is to lose your soul.”

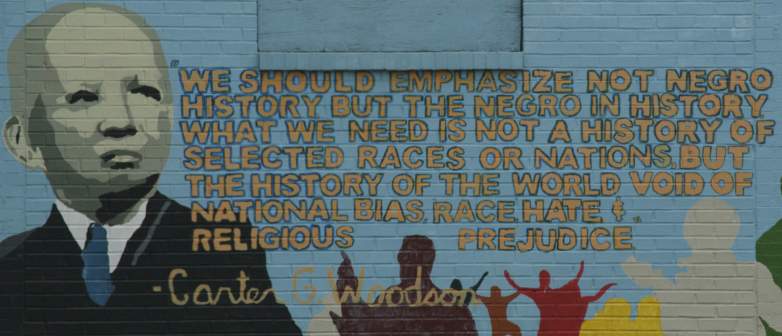

Woodson was once quoted as saying of black history: “We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in history. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world, void of national bias, race, hate, and religious prejudice. There should be no indulgence in undue eulogy of the Negro. The case of the Negro is well taken care of when it is shown how he has far influenced the development of civilization.”

2. Woodson Was the Second African-American to Ever Receive a Harvard University Doctorate Degree

Carter Woodson.

After high school, Woodson’s thirst for education remained. He was a pioneer in higher education. He was also a well-traveled man. “From late 1903 until early 1907, Woodson worked in the Philippines under the auspices of the US War Department. Woodson then traveled to Africa, Asia, and Europe and briefly attended the Sorbonne in Paris, France,” notes Blackpast.org.

However, in later years, Woodson would make his mark in the halls of academe. “Woodson went on to earn a master’s degree from the University of Chicago, after which he became the second African-American ever to receive a doctorate from Harvard University. He was also one of the first scholars to focus on the study of African-American history, writing over a dozen books on the topic over the years,” Torres wrote. The first African-American to ever receive a doctorate from Harvard? W.E.B. Du Bois.

He founded the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History in 1915 and “founded the Journal of Negro History in 1916.”

Woodson once said, “If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.” He also is quoted, in a comment that is more controversial, as once saying, “If the Negro in the ghetto must eternally be fed by the hand that pushes him into the ghetto, he will never become strong enough to get out of the ghetto.” You can read the context of those words here.

3. Woodson Founded a Black History Week in the Month That Frederick Douglass & Abraham Lincoln Were Born

Carter Woodson.

Woodson is honored at the start of Black History Month because he was so instrumental in bringing recognition to the importance of black history and founded a week that evolved into the month. According to Google, he worked to ensure that it was “taught in schools and studied by other scholars. He devised a program to encourage this study, which began in February of 1926 as a weeklong event.”

This event would later be expanded into Black History Month. “Woodson chose February for this celebration to commemorate the birth months of abolitionist Frederick Douglass and President Abraham Lincoln. This program eventually expanded to become what we know today as Black History Month,” noted Google. Douglass, the great abolitionist and thinker, was born on February 14, 1818. Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809.

According to the Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American Museum, the week initially had a different name. “In 1915, he and friends established the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. A year later, the Journal of Negro History, began quarterly publication. In 1926, Woodson proposed and launched the annual February observance of ‘Negro History Week,’ which became ‘Black History Month” in 1976,'” the museum says.

Woodson “lobbied extensively” to give black history month a national reach.

4. Dr. Woodson Was a Prolific Author

As part of his efforts to record black history, Carter Woodson became a prolific author. According to the museum that bears his name, “Dr. Woodson was the founder of Associated Publishers, the founder and editor of the Negro History Bulletin, and the author of more than 30 books. His best known publication is The Mis-Education of the Negro, originally published in 1933 and still pertinent today.” That book is often required reading at schools throughout the United States.

Woodson also took his writing abilities to the pages of newspapers. “Woodson wrote several hundred essays in leading black newspapers such as the New York Age, the Pittsburgh Courier from Pennsylvania, the Afro-American from Baltimore, Maryland, and the Chicago Defender,” reports Blackpast.org.

He once wrote of education: “For me, education means to inspire people to live more abundantly, to learn to begin with life as they find it and make it better.” He also wrote: “The author takes the position that the consumer pays the tax, and as such every individual of the social order should be given unlimited opportunity to make the most of himself.”

5. Woodson Wished There Would Come a Day When America Didn’t Need Special Days to Honor Black History

According to the NAACP, Woodson longed for a day when America didn’t need a Black History Month – or week. “Dr. Woodson often said that he hoped the time would come when Negro History Week would be unnecessary; when all Americans would willingly recognize the contributions of Black Americans as a legitimate and integral part of the history of this country,” wrote the NAACP.

His extraordinary contributions to American history influenced other historians; the NAACP writes that they include John Hope Franklin, Charles Wesley, and Benjamin Quarles. “Whether it’s called Black history, Negro history, Afro-American history, or African American history, his philosophy has made the study of Black history a legitimate and acceptable area of intellectual inquiry. Dr. Woodson’s concept has given a profound sense of dignity to all Black Americans,” the NAACP wrote.