Wisconsin courts What was Brendan Dassey's iq?

Much has been made about the cognitive challenges faced by Steven Avery’s nephew, Brendan Dassey, whose videotaped confessions in the Teresa Halbach murder were challenged aggressively in court.

Although a federal appeals court eventually ruled the confessions were voluntary (rejecting a lower panel and magistrate’s opposite conclusion), they are expected to be featured front-and-center in arguments in Making a Murderer 2 that Dassey did not get a fair shake. (You can see crime scene photos from the case here.)

Both Dassey and Avery were convicted in Wisconsin courts in 2007 in the murder of Halbach, a photographer whose bone fragments were found in a burn pit and barrels behind Avery’s trailer on the family junkyard property. The confession tapes were also featured in the first Making a Murderer series on Netflix, sparking outrage with many viewers who believed Dassey was a malleable and cognitively challenged youth (he was 16 at the time.)

The two cases were very different in some ways; Avery was convicted on forensic evidence – such as his blood in the victim’s car, which was found on the junkyard property where he, Dassey and other family members lived – and circumstantial evidence (he had an appointment with her that day). However, he never confessed and has always adamantly denied murdering Halbach. However, there was no forensic evidence tying Dassey to the murder (other than bleach spots on his pants; he told authorities Avery asked him to clean up a fluid in the garage the night Halbach disappeared.) Instead, Dassey’s conviction rested almost entirely on those confessions.

Exactly how cognitively disabled was Brendan Dassey, though? There’s no question that on, videotape, his affect is bizarre. He’s Forrest Gump-like, has poor eye contact, mumbles, and appears to give in and switch his answers with the slightest pressure. He starts out by saying he didn’t do it, and then slowly morphs into agreeing that he did. At times, the interrogators provide him details first, and then he says things like “yeah.” He later recanted it all.

However, he is also exceptionally detailed at times. There are times when the investigators ask him open-ended questions, and he responds with grisly and disturbing details. There are places where the cops seem to be leading Dassey. And there are places where they don’t. Throughout it all, though, they are clearly psychologically manipulating him. Pretending to be his friend. Promising him that things will be better for him if he talks. Pretending they know information they don’t.

Here’s what you need to know about Dassey’s IQ:

Brendan Dassey’s IQ Tested Higher Than Steven Avery’s

The following information comes from Manitowoc County court records and trial testimony in the Avery and Dassey cases.

Those records show that school officials had not labeled Dassey cognitively disabled. They had him in regular as well as some special classes. His IQ tested higher than Steven’s in tests administered by a defense psychologist.

Still it was low. And he clearly had problems that the school also repeatedly noted.

Kris Schoenenberger-Gross was the psychologist at Mishicot High School. The school had a file on Brendan. One report said, according to trial testimony: “He exhibits difficulty responding clearly and concisely to others. Paragraph comprehension, defining vocabulary and understanding age-appropriate vocabulary terms remains challenging. Brendan will occasionally ask questions when he is unsure. However, eye contact and participation during discussions with adults and peers is limited. Brendan’s memory, specifically is affecting all areas of language.”

“Brendan continues to demonstrate delays in his basic reading, reading comprehension and language skills, both receptively and expressively. Brendan needs specialized instruction which the regular education environment alone does not provide. He needs special education services and supports to help him be successful in school and to help meet his needs.”

“Uses minimal eye contact, gestures, and a variation of pitch in conversations in therapy and in the classroom. Willingly participates in speech and language therapy sessions.”

“Overall, Brendan demonstrates significantly delayed, receptive and expressive language skills, memory, short-term memory, immediate memory and working memory, vocabulary, sentence comprehension, pragmatics and areas of abstract language. For example idioms… Brendan’s strengths are in his willingness to participate in speech therapy, knowledge of famil-iar sequences and his articulation skills.”

“Brendan will occasionally ask questions when he is unsure, however eye contact and participation during discussions with adults and peers is limited… Brendan is expressionless, no facial expression, seemingly blank stare, possibly indicating daydreaming.”

Brendan was in regular classes at Mishicot, though, although he was receiving some special classes in speech or language.

“Was he the kind of student that your school district considered cognitively disabled?” asked the DA Ken Kratz.

“No,” said the school psychologist.

“And although he was getting some special classes in speech or language, Brendan pret-ty much, um, was a normal kid? That is, uh, went through normal classes in Mishicot, is that right?”

“Yes.”

He was tested on his thinking ability and scored 93 where the average score was 90-109. He was tested on his math skills and scored 100-102, when average was 90-110. He was in solid average range and wasn’t a behavioral problem at Mishicot. The school had never noticed problems with Brendan being easily influenced. He read at a fourth grade level. On another test, he’d scored below average to borderline range in short-term memory abilities.

A defense psychologist later administered IQ tests to Brendan. He found that Brendan’s IQ was on the “lower end of low average.” An average IQ was 100. Brendan’s IQ was 83 (higher, though, than Steven Avery’s, which was reportedly 70.)

The psychologist, Robert Gordon, of Janesville, Wis., also gave Brendan a test designed to measure “suggestibility.” Under pressure, how much would Brendan “yield” in his answers? Gordon found evidence of suggestibility. Brendan also scored high for social alienation and introversion. He was average on some measures. He was shy, deferential and passive. On the suggestibility test, Brendan answered in a “yielding fashion” 8 out of 15 times. He shifted his answers in 9 out of 20 potential questions. The test measured whether Brendan would shift his answers or yield to mild pressure or mild criticism. That was higher than average. As an example of a shift/yield in the March 1 interview, Gordon focused on passages like this one:

Investigator Tom Fassbender, “So Steve – Steve stabs her first and you cut her neck.”

Brendan nods, “Uh, yes.”

“What else happens to her in her head?”

Fassbender, “It’s extremely, extremely important you tell us this for us to believe you.”

Investigator Mark Wiegert, “Come on Brendan, what else?”

Pause.

Fassbender, “We know. We just know. You need to tell us.”

Brendan, “That’s all I can remember.”

Wiegert, “All right. I’m just going to come out and ask you, who shot her in the head?”

Brendan, “He did.”

Wiegert said in court that he didn’t really worry about Dassey having “cognitive limitations when he did the interview.”

“No. He was a mainstream student at Mishicot High School. He was in driver’s ed. He could answer questions. He could understand,” he testified. The defense counted more than 75 times in one interview in which Wiegert or Fassbender said something to Dassey either suggesting or directly stating that he was a liar.

Prosecutors told the jury that people often confess the way Brendan did. Almost no one pops up and volunteers “yeah, it was me!” Instead, people usually deny all at first. Then, they reveal bits and pieces, but they minimize their involvement. Such, as, saying, I was just a witness. Then, they sometimes, if authorities are lucky, become more detailed in ways that allow police to corroborate what they are saying with physical evidence or to see which details were withheld from the general public and only the killer would know. Confessions were more reliable in people with low IQs when they involved “event memory” – something the person actually lived through versus book memory. Details mattered.

Confessions usually tumbled out in waves. And coerced confessions usually come out after days-long interrogations, not hours long as this was, or they’re the result of physical beating, which wasn’t present here, prosecutors argued, court documents said.

Courts Disagree

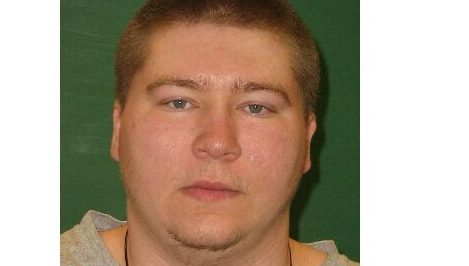

Brendan Dassey.

U.S. Magistrate judge William Duffin found that Dassey’s cognitive state and promises from investigators made the confessions involuntary. He found that Dassey’s conviction was predicated on “false promises” by interrogators, and the judge cited “Dassey’s age and intellectual deficits” in the decision. In a 91-page decision overturning Dassey’s conviction, Duffin found that the “investigators’ actions amounted to deceptive interrogation tactics that overbore Dassey’s free will.”

U.S. Magistrate Judge William Duffin. State Bar of Wisconsin.

“Especially when the investigators’ promises, assurances, and threats of negative consequences are assessed in conjunction with Dassey’s age, intellectual deficits, lack of experience in dealing with the police, the absence of a parent, and other relevant personal characteristics, the free will of a reasonable person in Dassey’s position would have been overborne,” wrote Duffin.

The case then went to an U.S. Court of Appeals panel for the 7th Circuit. They upheld the magistrate’s decision with a 2-1 ruling.

The state of Wisconsin appealed the magistrate’s decision. “We believe the magistrate judge’s decision that Brendan Dassey’s confession was coerced by investigators, and that no reasonable court could have concluded otherwise, is wrong on the facts and wrong on the law,” said Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel in a news release. “Two state courts carefully examined the evidence and properly concluded that Brendan Dassey’s confession to sexually assaulting and murdering Teresa Halbach with his uncle, Steven Avery, was voluntary, and the investigators did not use constitutionally impermissible tactics.”

Calumet County Sheriff’s Investigator Mark Wiegert and Wisconsin Department of Justice Special Agent Tom Fassbender interrogated Dassey, who was a juvenile, without his parent or defense attorney present, the court decision says.

The panel did not have the final say, however. The case then went before the full 7th Circuit appellate court for review. That court ruled 4-3 against Dassey, overturning the magistrate and upholding his conviction in an appeal that rested on the lawfulness of the law enforcement interrogations of him.

The full court relied on its belief that the underlying Wisconsin state appeals court – which had upheld Dassey’s conviction – acted reasonably in doing so. “The state court’s finding that Dassey’s confession was voluntary was not beyond fair debate, but we conclude it was reasonable,” the court wrote.

The court also found: “Dassey spoke with the interrogators freely, after receiving and understanding Miranda warnings, and with his mother’s consent. The interrogation took place in a comfortable setting, without any physical coercion or intimidation, without even raised voices, and over a relatively brief time. Dassey provided many of the most damning details himself in response to open‐ended questions. On a number of occasions he resisted the interrogators’ strong suggestions on particular details. Also, the investigators made no specific promises of leniency.”

You can read the opinion in full here.

Dassey’s lawyer, Laura Nirider of Northwestern law school’s Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth, said in a statement:

“The video of Brendan’s interrogation shows a confused boy who was manipulated by experienced police officers into accepting their story of how the murder of Teresa Halbach happened. These officers repeatedly assured him that everything would be ‘okay’ if he just told them what they wanted to hear and then fed him facts so that Brendan’s ‘confession’ fit their theory of the crime. By the end of the interrogation, Brendan was so confused that he actually thought he was going to return to school after confessing to murder.”

In June 2018, the United States Supreme Court declined Dassey’s request to review the federal court’s decision reinstating his conviction. The Supreme Court did not provide a reason for its decision.