Daniel Prigge wouldn’t have called himself a hero, his brother and close friends agree. When the subject came up, he deflected such superlatives, despite the two purple hearts from Iraq and 95 surgeries, despite the shrapnel in his stomach and the protruding bone in his calf, despite the fact that it hurt even to walk, despite the traumatic brain injury and PTSD and the partial blindness in one eye.

“He would not have called himself that; the heroes are the ones who didn’t make it home,” Bethany Gomez, a correctional officer at a Wisconsin prison who knew Prigge well, says. But she adds: “I did consider him heroic because, through everything, all he wanted to do was get out there and help his team and help his guys. That selflessness is what I think is heroic.”

“I would agree with her. He’s 100 percent a hero to me,” says David Prigge, his brother. “A hero is someone who puts others first; he (Daniel) really isn’t one to call himself a hero. He always said that he wasn’t a hero because those who died are the heroes, but to me a hero is someone who puts everyone first before him; it’s all-out selflessness.”

“I think Dan would say, ‘Stop talking about me,’” shares his friend Alex Witt, an Iraq veteran who helps run two veteran-focused and owned businesses, a protein bar company named Battle Bars, where he’s CEO, and a fitness gym in Illinois called 10.40.10 Fitness that he founded. “He would start talking about the people who don’t make it back. He was very adamant about not being called a hero. He wanted people who didn’t make it back to be remembered, and he wanted people in the community to know the positive things veterans are doing and what sacrifices they made.”

On March 29, 2020, Prigge, age 31, became one of those service members who, in a way, didn’t come back from Iraq, although he didn’t die there. His body, ravaged from the wounds of two combat deployments and likely filled with the prescription medications he needed to handle the pain from them, simply decided to give in, Gomez believes. “I’m the one who found him,” Gomez says. She thinks he died around 2:45 p.m. He texted her maybe six minutes before, writing that he loved her and didn’t want her to “be sad.” He was thankful for the great times she had given him. He was having nightmares that entire week and told her he sensed something bad was going to happen, but he wasn’t quite sure what.

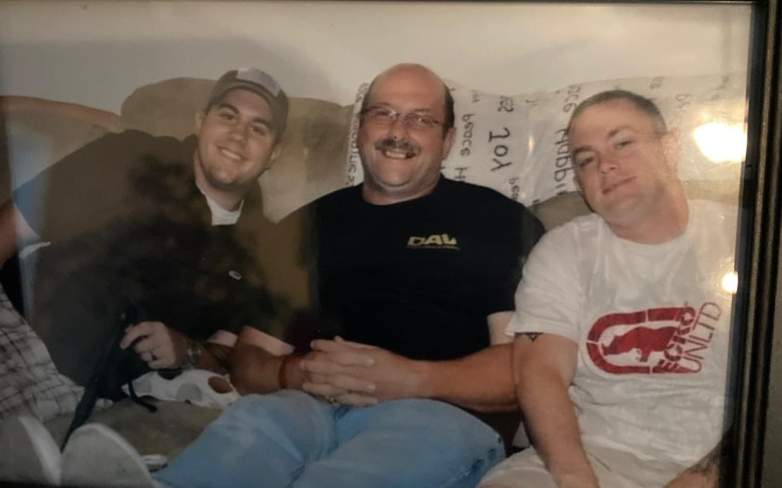

family photoDaniel Prigge

“He always said he didn’t want to be thought of as a hero because there were servicemen and servicewomen who made the ultimate sacrifice and they should be labeled as such,” Witt says. Then, he says, as if speaking to Prigge, “Now you’re a hero by your own terms!”

“Daniel was an amazing person who would give his shirt off his back, loved family and would hold people close to his heart,” said Annabell Prigge, who married Daniel after meeting him in North Carolina and who worked as a paramedic. “Daniel knew what it took in life to not just treat others the way he would like to be treated, but always made sure everyone was happy before him.”

Daniel Prigge (r) with his siblings Stacy Hopf and David Prigge.

At first, Gomez thought he’d choked to death when she found him lying face down on the floor with graham cracker crumbs on his sleeve. The medical examiner’s toxicology report and cause of death are pending, but choking was ruled out, she says. She thinks his body was too damaged to wake itself back up, with the prescription medication a factor. He was midway through a motivational Instagram post when he died. Gomez found it on his phone half completed near his body. He’d gone to the emergency room at St. Mary’s Hospital in Green Bay three times that week, she says, but was sent home to manage his pain with OxyContin because the hospital didn’t want to keep him there and risk him getting COVID-19 (he didn’t have COVID-19 himself, Gomez says).

“For all of you who think having a purple heart is something that’s cool, it’s not. This is real…,” he wrote. And then it cut off.

Gomez thinks he intended to write “this is reality.” With it, he was going to post a photo showing him throwing up blood in the toilet. Prigge’s sister Stacy Hopf says his injuries were so massive, and the battle he was still fighting so great, that “he was in the body of an 80 year old. For him to do a lot of things, it was very painful for him.” The PTSD was difficult too; he would wake up from nightmares and didn’t like large crowds. She said he also had 50% blockage in his heart but that didn’t kill him.

Gomez thinks she knows what Prigge would have continued writing because she knew him so well, and he’d written posts something like that before. She thinks he was trying to say that being in the military is a sacrifice. He didn’t want people to focus on the violence or to think it was something cool. He believed military service was necessary, and he had the utmost respect for people who undertake it. It protects our freedoms. However, he wanted those who join to have a “clear view” of what it entails. He wanted them to know the reality. That it wouldn’t be easy. That it would come with a cost. It was a cost he was gladly willing to endure; he went back to Iraq even after being injured the first time. But it was a cost all the same, and he’d devoted his life’s energy to helping other veterans with struggles. “Enjoy life while you have it, for all we know it can end within a second!” he wrote on Instagram 26 weeks ago.

When a service member dies in combat, they’re often remembered with somber pomp and circumstance, at least in recent years. Press releases are issued, news stories are written, and communities mobilize. However, when a service member dies nine years after injury, on an apartment floor in Green Bay, Wisconsin in the middle of a Sunday afternoon, as Prigge did, there’s often less public acknowledgment; it’s a more invisible sacrifice to those outside the veteran’s closest circle. That’s even truer during a pandemic; as people quarantined and worried about an invisible enemy in a new war, there was another death worthy of remembering. “We lost an American hero,” says Witt.

Daniel Prigge died from the tolls of war. The “shadows of war” followed him, Gomez says, even as he tried to help others escape them. He’s far from alone. The number of U.S. veterans lost each day to reasons that aren’t old age is staggering, some 17 per day to suicide alone (Prigge’s loved ones don’t believe his death was suicide, however, but rather a compilation of his injuries and the medication prescribed to deal with them.) From 2007 to 2017, the veteran suicide rate increased almost 50 percent in the United States, according to the Military Times. A research study in Military Medicine found: “The second U.S. invasion of Iraq—Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)—began on March 19, 2003. In the ensuing 6.5 years, the U.S. military sustained over 3,400 hostile deaths, 800 nonhostile deaths, and 31,000 wounded in action (WIA).” It’s believed those figures don’t begin to truly reflect the number of veterans from Iraq (and Afghanistan) with health issues due to their service. In 2013, the International Business Times reported that “more than 900,000 service men and women had been treated at Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals and clinics since returning from war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

Annabell believes the turning point came in January when he had an emergency life-saving stomach surgery. “He was getting tired. His body went through so much anesthesia, procedures, blood loss, weight loss, unable to eat, pain and suffering from the end results of fighting for so many years,” she says.

A Veterans Administration study in 2015 found that almost one-fourth of veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan had PTSD. They have higher rates of respiratory problems. Seventeen percent have traumatic brain injury. We’re talking about a lot of people because 2.77 million service members served in both wars. (The Brown County Medical Examiner’s office would not release Prigge’s cause of death to Heavy.com, requiring an open records request for a report it said would likely be redacted. That request is pending; the family says the COD is not yet known because of pending toxicology tests.)

“The military was a way of life for Daniel,” Annabell said. “He was a proud Ranger who fought for his family, the country and protecting what he loved. Having grown up in a military household he wanted to follow into his fathers footsteps and make him proud, serve his country and fight with his brothers to be part of a team.”

Prigge was born and raised in Berlin, Germany, and “moved here to the U.S. with his German mother, brother and father to South Carolina where his father retired from the military,” she says. “His father and mother were a large influence in his life, and he joined the military at 17 to follow into his father’s footsteps. Daniel has accomplished so much in his career with ease, became a Ranger, infantry man and enjoyed being with his brothers overseas.”

“I think he was very humble. He just wanted everybody to know the story that the military was such a big part of his life,” says Hopf, on whose Sheboygan County, Wisconsin farm Daniel lived for a time after leaving the military. Hopf described the family’s military roots as going back to the Civil War, with their father and grandfather also serving.

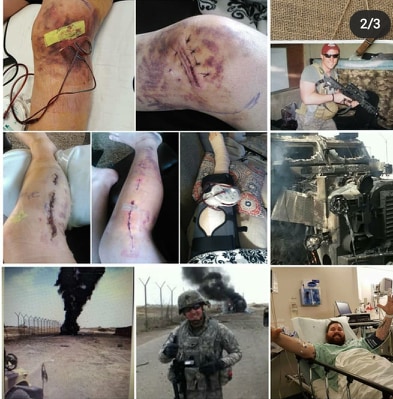

Prigge frequently detailed his injuries on Instagram, the number of surgeries growing with the months and years.

“Yesterday I was rushed in sooner for my 62nd surgery! They reconstructed my clavicle, shaved down the bone and fixed the dislocation. They also found a hematoma where my tib fib is fused and my fibula is cut in half,” Prigge wrote in one post. “They cleaned that out and took all scar tissue out and also went into my knee joint and cleaned that out as well. I do not recommend doing two parts of your body at once, but seeing that I have this many surgeries, it needed to be done because it’s not good to have anesthesia that many times. I want to thank everyone for the support.”

Daniel Prigge

Explains Annabell: “There were roller coasters of getting well, new developments, to six knee surgeries in one year and being confined to a wheelchair for six months out of that year, but he never lost hope. Always a smile, never wanted to show his pain, and know he has endured so much not even 20 people in a lifetime should go through. His last couple months have been a hard struggle from emergency stomach surgeries to fighting for his life. Several blood and iron transfusions, medical appointments, procedures, and days of severe sickness, losing 60 pounds, always vomiting, never being able to eat – Daniel still fought to stay alive.”

Even with all of that, he felt there were others who went “through much worse.” He’d lost 16 friends who went through worse.

“Although I am going through pain and a long recovery, I know there are soldiers and civilians out there going through much worse. So I have nothing to complain about and I am just happy for being here. There are many soldiers I have lost, (PFC Robert H.) Dembowski and 15 other soldiers of mine aren’t here to have a chance to even have these feelings,” he wrote.

“I have lost 16 men from a mixture of being a casualty in Iraq and suicide. I will push on and keep going for those incredible men. Heaven received the best damn team guys ever. If you’re going through something tough, I promise you will make it through and survive. Just keep pushing and use the time we have on earth to better yourself and the bigger picture that is bigger than all of us. One guarantee in life is that we all will pay the man, when that times comes, which can be at any moment.”

The post concluded: “Will you be satisfied with what you did and your legacy you will leave behind?”

Two Friends, Lost

One of the 5 Dallas police officers shot in the sniper ambush attack was a young father by the name of Patrick Zamarripa.

Alex Witt already understood what it means to endure the pain of losing a friend. His best friend Patrick Zamarripa served three tours in Iraq but died with four others at the hands of an active shooter while wearing the uniform of the Dallas police on the streets of an American city. There was wall-to-wall national news coverage. It was a summer of police shootings, 2016, and they dominated the news. When Witt speaks of Daniel, 31, his words echo those he used to describe Patrick, who died at age 32, describing a similar ethos. Their love of country and affinity for military brotherhood. The devotion to service and embodiment of sacrifice. How they made it back from Iraq only to lose their lives here. When Patrick died, Witt told the news media how Zamarripa “loved his country and would do anything for citizens in it.”

Pat Zamarripa

In the days after Prigge’s sudden death, Witt has been as singularly determined to make sure that this friend is also not forgotten.

Witt’s gym and protein bar company are dedicated to helping and being a safe space for veterans, with a “focus on honoring the military and first responders and the community we serve.” He wanted to find a way to tell the stories of people like Patrick, he says, to “honor this guy, this awesome human being.”

Alex Witt

He also understands that, if you make your life’s focus helping veterans, there are going to be more sad moments of loss. He befriended Prigge, who came to his gym to speak in a motivational sense to others about his military experiences, and surviving the aftermath, and they fell into an easy and familiar camaraderie. In the whole time they were friends, they barely talked about so-called “war stories.” They talked about their lives. Although they didn’t serve together, by the end, Witt almost felt like he had served with Prigge. It’s important to many service members to recreate the tight bonds of brotherhood here that they experienced overseas, a support system made tougher to do in a world of social distancing.

Alex Witt

“He needs to be remembered,” Witt says now of Prigge, in a phone call from Illinois. “This man’s name should be known.” He put together a video to help make sure that happens. “Dan is our WHY. WHY we become leaders in our community, WHY we help the person next to us improve. WHY we lead with integrity,” he wrote on Instagram with it. “This past Sunday night, we lost an important member of our family, Daniel Prigge. Dan was a two-time Purple Heart recipient, Army Ranger, and overall great human being who lost his battle after 95 plus surgeries he sustained over the years protecting our freedom.”

In the video, Witt reads part of a recent text Prigge wrote him: “We met for a reason, and I am proud to call you my brother.” On Instagram in March, Prigge wrote about a visit to Witt’s gym: “As I lay here and prepare for my 93rd surgery, I am thinking of all the badasses I met this past weekend in Chicago! @10.40.10_fit is a gym where you walk in as an individual, but you leave as a family with brothers and sisters that have your back.”

Chef Andre Rush, a former military chef known for his work on suicide prevention and advocacy of military service, spoke in the video. “Daniel inspired me… everything he gave back to the community. I am humbled to have called him a friend, and he will always be remembered.” He called him an example of “selfless service,” of leadership, and “just a downright kind human being.”

Annabell says, “Daniel always lit up any room he entered, had a smile and immediately made everyone feel comfortable and become instant friends. Anyone who met Daniel will always remember that spark that he had and would help anyone and everyone. Daniel loved helping other veterans who were recently injured and being someone they can always come to. He helped through his veteran speeches, being part of local programs.” She said they signed up for a May treatment program in Florida called Veterans Alternative “to help with his nightmares, PTSD, sleeping, and find a way to connect back to what life meant, could be and find his will to remain strong.” But he didn’t make it until May.

A Casualty of War

Daniel Prigge

Prigge died in the middle of a national pandemic with a media and public that were fixated on and, understandably, frightened by a novel coronavirus. His story is the age-old tale of the wounded warrior who saw too much, took very little credit for it, and gave all. His story is remarkable through the sacrifices he made and the manner in which he dealt with them, reaching back into the veteran community to help those he could.

“I do think he’s a casualty of war; even though he died of his injuries, his wounds, he suffered those injuries from combat,” says David Prigge, who, like his only brother, also served in the military and returned with an internal heart monitor from an IED attack.

Witt doesn’t shy away from giving Prigge that hero label. “His picture should be listed underneath the word,” says Witt. “Not just because of him serving overseas, the combined effort of that, but because, when he left there, he continued doing things to help other veterans who are struggling. The guy responded to people at 2 in the morning in excruciating pain, talking people off the ledge. People who he had no idea who they were. Coming to our gym, he was very quiet and reserved and always had a smile. But you don’t know how much pain he was in talking to people. Long conversations hurt his body. You’d never know it. He cared so much about getting the word out about the sacrifices people make. To me that is what heroes are. Guys like him. The spirit he had was so contagious.”

Prigge, with his brother and father, David Prigge Sr.

“He loved America completely and he loved Americans and he never wished violence on Americans whatsoever,” Gomez says. “He never wanted Americans to see violence. He fought fiercely at his brothers’ sides. Everything was for them. He was extremely family oriented…he created a family with his military brothers.” He appreciated first responders of all sorts.

In January 2020, Prigge underwent stomach surgery where they cut through his abdominal wall, leaving even walking painful.

The day after he was discharged from a hospital in New York for one of his many surgeries, where he’d been working a security contract assignment, he walked 10 miles to see Ground Zero and then walked 10 miles back. His father, also a military man, knew some of the people whose names were on the wall. “Ground Zero was very emotional for him,” says Gomez. David says Daniel, who entered the Army right out of high school as a teenager without ever considering another calling, was motivated to service in part by the horrors of 9/11.

“All those names on that memorial, I’m sure each of them would be happy to be here and go through everyday life struggles along with us,” Prigge wrote on Instagram, sharing a photo of himself at the memorial. “Enjoy what time we do have left, there is only one guarantee in life and that is we all will face the music and have to leave our loved ones. So let’s use this short time we have wisely and enjoy it. If you ever need help, reach out to me anytime.”

“He had an immeasurable drive for serving the public and serving the military,” says Gomez.

Remembering Debo

PFC Robert H. Dembowski Jr.

Like Witt, Prigge understood how it feels to watch a friend die too soon. When Prigge spoke of people who didn’t make it back, he was often thinking of Robert Dembowski, loved ones say. They called him Debo. Debo, a Pennsylvania soldier described by his mother as a person who “would put everyone ahead of him. He always put the veterans before him,” took a bullet from a sniper to the neck while dragging Daniel to safety behind a car when their convoy was hit in Iraq. He fell on top of him, exhaling his final breath.

“Debo never left him. He made a promise to Debo,” Gomez says. “He had a conversation with Debo while Debo was dying on his chest that was just for him. If it wasn’t for Debo, he wouldn’t be there.” The exact nature of that conversation was something Prigge was determined to take to his grave. And he did. Now Gomez wears the bracelet Prigge wore in honor of Debo. “He sheltered him from a firefight,” Gomez says of Debo. “Unfortunately, it was with his body.”

In May 2019, Prigge wrote on Instagram, “Sitting up at night missing you brother, in just a few days will be our anniversary and I cant get that day out of my head tonight! Thanks for everything you did for us that day! Love you Debo!!”

A memorial fund in the Pennsylvanian’s name says, “Bob died May 24, 2007 of wounds suffered when his unit came in contact with enemy forces using small arms fire near Baghdad, Iraq….Bob’s respect for his country and its veterans had an impact on all who came in contact with him.”

Debo was on Prigge’s mind when he ran a 20-mile race for veterans called the H.O.O.A.H Wisconsin race, which stands for Helping Out Our American Heroes. He carried his purple hearts and ended up in the hospital later because of the stress running put on his wounds. He ran for Debo.

Prigge with his family: Brother David and their mother, Lottie Prigge.

When Daniel would battle against the pain – from the nearly eight dozen surgeries, from the shrapnel sprayed throughout his stomach that left him unable to eat solid food, from the PTSD and the TBI, from the tremors, and the partial blindness in his left eye – he would mention Debo. He would have had every right to complain about the pain. Gomez woke in the middle of the night repeatedly to make sure he was still breathing. She gave him the Heimlich maneuver several times when he started choking during the week before he died. He was supposed to be on a completely liquid diet, but sometimes he still wanted to eat Graham crackers. Sometimes he would dry heave like he was going to vomit, but he couldn’t vomit because his diaphragm and esophagus were wound around his stomach due to a long-ago surgery. It was starting to come loose. There was a perforation in his stomach too.

None of this, he told Gomez, gave him a right to complain, and so he didn’t. He was here, Prigge would repeat. Debo was not.

He wrote on Instagram last year:

In 2011, I was struck by multiple EFP’s, RPG and small arms fire and I just received the paperwork that will be sent to the VA. I have been through 84 surgeries thinking this whole time it was only 62. I say this not to get sympathy, but to let each and every one of you know that there is a light at the end of the tunnel. I have injuries from not walking for two years, being blind in one eye, brain leakage, shifted spine, herniated and bulged disc with tears, all patella ligaments torn, torn meniscus, torn MCL, torn ACL, fascia removed, fibula cut in half, tib fib fusion, over 6 fusions with more to come in my back and neck, 4 nose reconstruction surgeries, stomach cut in half with the rest of stomach wrapped around esophagus and diaphragm, shoulder reconstruction and many more. No matter what injuries or problems you have, there is always a way to get past and push through. Reach out for help, there is nothing wrong with receiving help. I have been though the darkest days of my life and if I didn’t have help, I probably wouldn’t have had the motivation to push on. If you need someone to talk to then you can reach out to me also. I will always be there for you all…

Gomez says the pain grew so severe by the last week of Daniel’s life that he told her in one rare moment that he would prefer to be “blown up again,” which was saying a lot for a guy who steadfastly refused to complain, and he was coughing up blood again, and he went to the emergency room three times at a Green Bay hospital. But she says the hospital sent him home with a “giant bottle of pills,” opioids she thinks, because healthcare professionals were worried that Prigge might get COVID-19 if he stayed in the hospital for pain management. He was supposed to have surgery the Monday before he died, but his stomach was too scarred to tolerate it, so they wanted to wait. They sent him home. He came back. They sent him home. He came back again. They sent him home again. He died there.

It’s not just veterans, says Gomez. She thinks a lot of people probably aren’t getting adequate medical care because the hospitals are so overwhelmed by coronavirus.

“This coronavirus made it hard not only for veterans but for everyone to get adequate care. You have to basically be dying to even be taken seriously at the emergency room because people are being turned away and told, ‘If you’re healthy, go home and self-medicate,’” Gomez says.

Heavy.com contacted HSHS St. Mary’s Hospital Medical Center for reaction. The hospital’s spokeswoman says St. Mary’s can’t comment on individual cases, but added, “The safety and well-being of our patients is the top priority at all times at HSHS St. Mary’s Hospital Medical Center, and amid this pandemic we continue to provide the same level of high-quality emergency care our community trusts and relies upon. Our clinical processes have not changed and we are more than prepared to care for patients experiencing any level of emergency, including those related to COVID-19 and those not related to COVID-19.”

‘He Would Do it 1,000 Times Over Again’

Family photoPhotos of Daniel’s injuries.

Despite all that he and his brother gave, David says he’d go back into the military in a heartbeat. “For this COVID-19, they’re asking retired veterans if they want to come back in to help with it,” he says, but they’re looking for specialties he doesn’t have, like medics and doctors. Otherwise, he says, he’d be right there. Daniel was like that, despite all. “He would do it 1,000 times over again,” insists David. “He didn’t think his fight was over. The motivation and the drive he had were just unbelievable.” He won’t get into politics or hindsight quarterbacking on Iraq, saying, “We go where they send us.”

What does he think Daniel would want people reading this story to know, especially if they are veterans? “He would tell any veteran no matter what they are going through, ‘You can call me any time of the day or night, and I’ll help you through it,’” David says, “A lot of veterans look up to that, and they took him on for his word and he was there for them. He would want other veterans to never give up. Don’t give up on life, don’t give up on yourself, there’s always tomorrow, another step to a better life. If you don’t give up, you’ll succeed.”

Daniel’s body was shattered inside but you wouldn’t know it from the outside. He seemed like just one of the guys. Meanwhile, he was quietly helping other veterans. Dropping everything for those with PTSD. Telling them they had to remain positive, his girlfriend recalls, and insisting they too could make it. Witt remembers how Daniel would stay up many nights messaging this veteran or that, talking them off this ledge or that, even while suffering great pain. He gave motivational speeches.

Daniel Prigge with his barbell at Witt’s fitness center.

David recalled how the brothers were “military brats,” growing up in South Carolina and Germany. David believes Daniel got his love of country and determination to serve from observing their father’s military career. Daniel served in combat twice, being injured both times, and asking to go back because he wanted to rejoin the other soldiers still there. Prigge wrote about the second injury in a blog post for the Purple Heart Foundation.

My name is Daniel Prigge, I served a little over 10 years in the US Army. I was wounded on May 03, 2011. My vehicle was struck by three EFP roadside bombs. My convoy was hit with a total of five EFP’s and one EFP that did not go off. My truck was also hit by an RPG and small arms fire during the ambush…I was the truck commander of the convoy, I was knocked out from the explosion and had sustained injuries of a shifted spine, both knees completely blown out and dislocated, left hemiparesis, broken nose, intestinal problems, brain leakage as well as shrapnel hitting my eye and destroying my optic nerve.

He retired from the Army in 2015 and opened a Max Muscle Sports Nutrition store in Green Bay, Wisconsin, while also working periodic security contracts.

He had a lot of good times along the way too. His loved ones remember his fun-loving sense of humor. He would go for a beer with Witt and shoot the breeze just like anyone else. If you looked at him physically, Gomez says, you would never, ever guess what was going on inside. “He was a goofball,” says Hopf. “He loved joking around.”

He was kind and wanted only kindness from others. He didn’t sugarcoat things and gave it to you straight. He liked to sing and dance to things like The Electric Slide but didn’t want anyone to know because Army Rangers aren’t supposed to sing and dance.

A Delayed Burial

Prigge had more than 44,000 followers on Instagram. He wrote a lot about service on that page. One post details his meeting with an elderly World War II veteran.

“When I do these speeches, I get to meet amazing people,” he wrote with the above photo. “This young man was in Normandy and was in the Navy. Such an amazing guy, almost pushing 100 years old and had to get up on stage and take a few pictures with me. We had such a great conversation and I feel so humble to have met this man and was very impressed to hear his story. His service will never be forgotten or taken for granted by myself. Just him saying, ‘I am getting on stage to take a picture with this young man,’ when he can barely walk definitely shows me how much this man loves veterans.”

His service will never be forgotten.

Prigge added: “We have a brotherhood that cannot be broken no matter what era we come from. If you see me, please stop, talk and take pictures. It is memories I will never forget and keep me grounded, humbled and actually does help me mentally. It helps me because it keeps me having that family feeling we as veterans have that only we will understand. Have a great Tuesday everyone.”

Prigge’s loved ones want to bury him in Arlington National Cemetery, but COVID-19 is delaying it. “I picked up some of his ashes at the funeral home at the beginning of week, and it was one of the hardest things I’ve had to do,” says his sister. “I had a necklace made for some of his ashes too.”

Witt remembers the last time Prigge came into his gym. He seemed like he didn’t want to leave. He hung around, talked to everyone. His name is now on a barbell there. Pat Zamarripa’s name is too. Witt mentions how first responders are coming back into the public’s attention again due to their heroics on the front lines of the COVID-19 fight, including the National Guard, along with doctors and nurses. He hopes that continues. He wants to make sure the stories of these quiet heroes continue being told.

“The shadows from the war follow them,” Gomez says. “I know he (Daniel) would tell veterans that if you need help seek it. Don’t think you’re too strong.”

“He made the ultimate sacrifice,” says Witt. “He would want to be remembered as someone who never, ever gave up regardless of how bad things were. Surgery after surgery, he just kept coming back. For the fight. It used to be Iraq, now it’s back here in the U.S. Helping transition veterans and first responders out there who need a boost. He cared about people who cared about this country.”

Annabell, too, considers him a hero: “Not just a hero for his distinguished brave and noble qualities, but also for the courage and ability to have fought for his country to fighting for his life in the end. He always wanted to go back to Iraq even after his injuries to help his brothers fight. He’s a hero for fighting through losing his best friend Debo in war, his injuries, wanting to get better for his family and always wanted to help others who also had injuries to show they can make it through.”

READ NEXT: Remembering the Life of Officer Patrick Zamarripa.