Hisaye Yamamoto was an American author who wrote about the Japanese immigrant experience. She is being celebrated with a Google Doodle in honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month.

“In honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, today’s Doodle celebrates Japanese-American short story author Hisaye Yamamoto, among the first Asian Americans to receive post-war national literary recognition,” Google wrote. “Throughout an acclaimed career, Yamamoto constructed candid and incisive stories that aimed to bridge the cultural divide between first and second-generation Japanese-Americans by detailing their experiences in the wake of World War II.”

Google Vice President of Marketing Marvin Chow said in a blog post, “This year, for Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Google is reaffirming its commitment to standing with the Asian and Pacific Islander community in the fight against hatred, while also honoring the diversity of different Asian cultures and elevating API voices. We’re doing this in part by launching a number of initiatives that uplift the API community through our products and in our own workplace.”

Alyssa Winans/GoogleHisaye Yamamoto is being celebrated with a Google Doodle.

Chow added, “We’re honored to grow our support for the organizations on the front lines fighting for safety, dignity and equity for the API community and have committed more than $10 million toward this critical work. … In recent months, I’ve been encouraged by how our Google API community has come together and how the company has stood against anti-Asian racism and hatred. And as I think about my own story and role as a father, I remain hopeful things can be different for my daughters and that they’ll feel a sense of belonging and inclusion which I, and so many others, have not.”

Here’s what you need to know about Hisaye Yamamoto:

1. Yamamoto Was Born in 1921 in Redondo Beach, California, as the Daughter of Japanese Immigrant Parents & She Spent Time in a Japanese Internment Camp

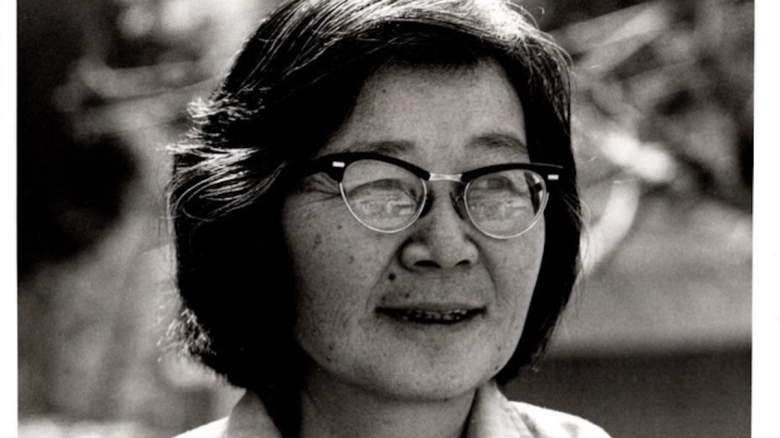

Yamamoto Family via GoogleHisaye Yamamoto.

Hisaye Yamamoto was born on August 23, 1921, in Redondo Beach, California, according to Google’s Doodle page. Her parents were immigrants from Japan. She was one of three children, along with her two brothers.

“Her parents were immigrants from the Kumamoto Prefecture in Japan and farmed strawberries to make a living in the United States,” according to the American Writers Museum. “Since they were not allowed to own agricultural land under the California Alien Land Law of 1913, Hisaye’s family moved from place to place while she and her brothers were growing up.”

According to the American Writers Museum, “Hisaye’s mother (pictured on the left) encouraged her daughter to write when she was young. Many of Hisaye’s short stories explore the issues faced between immigrant parents (Issei) and their children born in the United States (Nisei).”

Yamamoto told the museum, “I remember one of my favorite things in school was having the teacher read to us. I remember Wizard of Oz and Doctor Doolittle and stuff like that. I just loved it. I would check out as many books as they let me. So, I guess I thought writing was it, writing books.”

2. Yamamoto & Her Family Were Put Into a Japanese Internment Camp During World War II, Where She Was a Reporter for the Poston Chronicle

Yamamoto Family via GoogleHisaye Yamamoto.

According to the American Writers Museum, Yamamoto began publishing her writing as a teen. “By the age of 14, she had her own column in the local journal Kashu Mainichi. She wrote under the pseudonym Napoleon,” the museum wrote. She told the museum, “On weekends [the Japanese newspapers] would have a feature page, where people would send in all kinds of things. They’d print anything, so that’s how I got started.”

Yamamoto and her family were sent to a Japanese internment camp during World War II. According to Google, “Following the outbreak of World War II and due to Executive Order 9066, Yamamoto’s family was among the over 120,000 Japanese-Americans forced by the U.S. to relocate to government prison camps (aka Japanese internment camps), where they faced violence and harsh conditions. Despite the injustices encountered daily, she kept her literary aspirations alive as a reporter and columnist for the ‘Poston Chronicle,’ the camp newspaper.”

She and her family were interned at the Poston, Arizona, camp, in 1942 according to the Chicago Review. She and her brothers were moved to Massachusetts in 1944, but she was returned to Poston after one of her brothers was killed while serving in the military in Italy.

Yamamoto told the Chicago Review in 1993, “When I gave a talk at Yale, quite a few students made reference to the increased hostility toward Asians. I didn’t hear any specific references to Japan-bashing, but then I was there for the fiftieth-year observance of the internment, so I was kind of insulated, I guess, from non-Japanese attitudes. When I spoke at UC-Santa Barbara in February, some of the students and staff spoke of their apprehension when going out in public, because of the Japan-bashing and the increase in anti-Asian incidents generally.”

She added, “The U.S. has a long way to go in its treatment of minorities, including the descendants of the original inhabitants.”

3. Yamamoto, Who Started Her Writing Career as a Columnist for the Los Angeles Tribune, Is Best Known for Her Short Story Collection ‘Seventeen Syllables’

After being released from internment, Yamamoto, who graduated from Compton College, began her professional writing career as a columnist for the Los Angeles Tribune. The newspaper was Black-owned, according to the Los Angeles Times.

“Her experiences there deepened her awareness of racism to a point of nearly unbearable anguish. She wrote a story about the intimidation of a black family named Short by white neighbors in segregated Fontana. She attempted to hew to journalistic standards of impartiality, cautiously describing the threats against the family as ‘alleged’ or ‘claims,'” the Times wrote in her obituary. “After her story ran, the Shorts were killed in an apparent arson fire. Yamamoto castigated herself for failing to convey the urgency of their situation.”

The Times quoted her as saying in a 1985 essay, A Fire in Fontana, “I should have been an evangelist at Seventh and Broadway, shouting out the name of the Short family and their predicament in Fontana.” The Times wrote, “Instead, she pronounced her effort to communicate as pathetic as ‘the bit of saliva which occasionally trickled’ from the corner of a feeble man’s mouth.”

Yamamoto published several collections of short stories from 1948 until 1986, including Seventeen Syllables, The High-Heeled Shoes: A Memoir, Wilshire Bus, Underground Lady and A Day in Little Tokyo. King-Kok Cheung, a UCLA professor and literary critic, wrote in Articulate Silences that Yamamoto was, “one of the first Japanese American writers to gain national recognition after the war, when anti-Japanese sentiment was still rampant.”

Japanese American Dramatist Wakako Yamamuchi told the Times, “She wrote in a true voice. She wrote about what she knew and that was about us — Asians, Japanese Americans. Her stories were wonderful, beautiful legacies.”

Yamamoto told the Chicago Reader in 1993, “I guess I’m just writing to please myself, express myself, mainly, since I don’t know anybody’s ever going to read it. I’m just trying to put down whatever is stuck in my craw as best I can. You know, get it out of my system. I’ve never thought of writing for anybody. I don’t think you can write aiming at a specifically Asian-American audience if you want to write freely. No, you just express yourself without thinking of that angle.”

4. Yamamoto Was Married & Had 5 Children & Several Grandchildren

Yamamoto was married for 48 years to Anthony DeSoto until his death in 2003, according to her obituary. She and her husband had five children, Paul, Kibo, Yuki, Rocky and Gilbert, along with seven grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, her obituary said.

She was honored with the 1986 American Book Award for Lifetime Achievement, the 1989 Book Award from the Association of Asian American Studies and was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010 by the Asian American Writers Workshop.

In the announcement of that award, the Asian American Writers Workshop wrote, “Not unlike the fiction of Flannery O’Connor, Yamamoto’s stories are brutal, efficient fables of race, saturated with the social subtext of the American small town. Her work focuses on the normal lives of Japanese women — fully-formed characters described by Grace Paley as ‘gutsy and fragile’ — and the uneasy relationship between Japanese immigrants and their children, many of whom grew up speaking only Japanese until kindergarten but found themselves increasingly distanced from their parents’ way of life.”

The AAWW added, “While capturing the postwar intergenerational struggles and rustic cross-ethnic American West, Yamamoto’s stories always feel relevant to the present. They are edgy and never sentimental — a quality attested to by their motley, Chekhovian characters, which include an interned mentally ill ballerina, a Japanese American wife married to a white Christian alcoholic, an eye-rolling child of immigrants, and a naked man dressed only in high heels.”

5. Yamamoto Died at Age 89 in 2011 in Los Angeles

Yamamoto suffered a stroke in 2010 and died a year later, on January 30, 2011, in Los Angeles, according to an obituary written by the Los Angeles Times.

Yamamoto said in an interview in 1999 about her experiences in the Japanese internment camps, “I have a lot of anger inside me … I get it out in my writing. … I don’t think I’ll ever get over being angry about the internment, because under the proper circumstances, tears still come to my eyes, you know? … I see that stuff like that has gone on throughout man’s recorded history, so it’s just a general anger about injustice. … This happened in the United States, where we have a Bill of Rights, which was totally ignored in our case.”

Doodler Alyssa Winans said about her work honoring Yamamoto in 2021, “Reading Yamamoto’s work and working on this Doodle amidst all the recent news about rising violence hit especially hard. It’s difficult to see elements of history repeating itself, and my heart goes out to all the individuals and families that have been affected. As someone of mixed background, I have a complex relationship with different aspects of my culture, so I feel honored to be able to work on a Doodle for APAHM. I am always glad to see a space where Asian American and Pacific Islander voices, causes, and culture is elevated and celebrated.”

READ NEXT: Woman Gives Birth on Delta Flight, TikTok Video Shows [WATCH]