Fifty years ago, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was standing on the second-story balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, when he was gunned down by a sniper.

Only 39 years old at the time, King had, in the eight years that preceded his tragic death, transformed the American civil rights movement. It became a national crusade that inspired people from across the social spectrum and turned long-neglected economic and racial injustices into major political issues, not just in the United States, but around the world.

As a social activist, King’s greatest moment came in August 1963, when he helped to organize the March on Washington.

More than 250,000 people gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial to protest against segregation and bigotry, and King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

In the months that followed, younger and more militant members of the civil rights movement grew increasingly frustrated with King’s caution and his commitment to non-violent resistance, but King pushed on. And in the aftermath of his assassination, millions of people paid tribute to his courage, his eloquence and his determination.

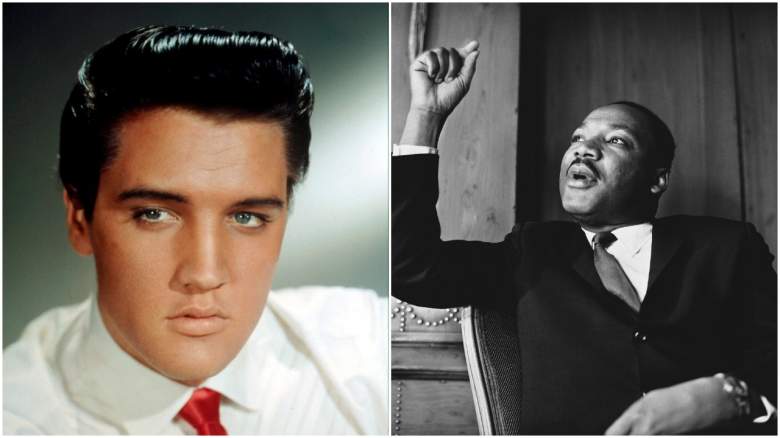

Elvis Presley was one of them. He recorded the song “If I Can Dream” just two months after the murder, and the emotional intensity with which he delivers it still brings back the shock and grief that gripped America in the wake of King’s murder.

Presley was just six years younger than King, and both were born and raised in the Deep South (King in Georgia and Elvis in Mississippi), where they were surrounded by institutionalized racism.

King was not a great admirer of rock ‘n’ roll, but Presley greatly admired King, who was killed less than nine miles from Presley’s home at Graceland.

Presley was unable to attend the funeral in person as he was filming Live a Little, Love a Little, one of his many movies. But according to his co-star Celeste Yarnall, she and Elvis “watched the funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr. together over lunch in his trailer. He cried. He really cared deeply.”

A few weeks later, Elvis began to work on the one-hour TV show now widely known as his ’68 Comeback Special. Filmed in June and airing in December, the show was originally scheduled to close with Elvis singing “I’ll be Home for Christmas,” a plan enthusiastically endorsed by his Machiavellian manager, Colonel Tom Parker.

But in light of King’s assassination (and, as production of the show got under way, the murder of Sen. Robert Kennedy on June 6, 1968), Elvis balked. He wanted to conclude with a song that reflected his deep sadness at the racial and political strife dividing the country.

Steve Binder, the director of the Comeback Special, agreed. “I wanted to let the world know that here was a guy who was not prejudiced,” Binder declared, “who was raised in the heart of prejudice, but was really above all that.”

Binder and Elvis were able to outmanoeuvre Parker, and for once Elvis got to sing what he wanted to sing. The Comeback Special closes — unforgettably — with “If I Can Dream,” written by the vocal arranger Earl Brown, and performed by Elvis in a white suit standing alone in front of large red letters that spelled out Elvis.

‘Why can’t my dream come true?’

King’s “I Have a Dream” speech is clearly Brown’s inspiration for the lyrics of “If I Can Dream.” Freedom, promise, redemption and darkness are at the crux of both, as the speech is variously echoed, adapted and rewritten in the lyrics.

King’s image of “a great beacon light” reappears in Brown’s reference to “a beckoning candle.” King’s “solid rock of brotherhood” corresponds to Brown’s vision of “brothers” walking “hand in hand.” King’s “sunlit path of racial justice” prompts Brown’s invocation of “a warmer sun / Where hope keeps shining on everyone.”

Above all, of course, both King and Brown “dream” of a better, more equitable society and future, though King’s optimism (“I Have a Dream”) contrasts sharply with Brown’s tentativeness (“If I Can Dream”).

Faced in 1963 with bigotry, gun violence and police brutality, King remains convinced that “somehow this situation can and will be changed,” and that “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Brown struggles to be as confident. Confronted in 1968 by the assassinations of King and Kennedy, his lyrics — unlike King’s speech — are suffused with “doubt and fear,” though he maintains that he is “sure that the answers gonna come somehow.”

King did not deny “the difficulties of today and tomorrow,” but he had the courage to imagine a better world in spite of them, and had already spelled out the cultural, legal and moral changes that needed to take place in order for us to create that world.

In response, Brown asks the most pressing question of all. If the example of King enables us to “dream of a better land,” and if we and millions of other people believe in that same dream, “why, oh why, oh why can’t my dream come true?”

Still, we dream

Brown’s lyrics are an impassioned reaction to the devastating news of King’s death, but it is what Elvis does with those lyrics that transforms “If I Can Dream” into what is, I believe, one of the most moving tributes ever paid to the bravery and vision of King.

For the first time in almost a decade, and for one of the last times in his career, Elvis is singing — and knows himself to be singing — a song that matters. His voice is full of raw emotion that seems at times almost to overwhelm him, and that drives him in the bridge (“the strength to dream”) and at the climax (“right now”) to an intensity that approaches a scream.

Before us once again is the angry, urgent, anti-establishment Elvis who exploded onto the American music scene 12 years earlier, and who now, at 33 years old, closes his Comeback Special by honouring the country’s greatest Black leader.

Less than a decade later, Elvis himself was dead, and while “If I Can Dream” has been recorded by several other artists, and included on a number of different Elvis compilations, no re-mastering or re-release can replace the power of the song in its original context.

Martin Luther King, Jr. urged us to dream. After his assassination, Elvis hopes that we still “can dream.” The death of King half a century ago reminds us of how far our society still is from the equality that King imagined.

As his words continue to inspire us to more unified and purposeful action, especially in the current political climate, so too they inspired Elvis, and the trembling, soaring voice with which he sings “If I Can Dream.”

‘If I Can Dream:’ Lyrics

There must be lights burning brighter somewhere

Got to be birds flying higher in a sky more blue

If I can dream of a better land

Where all my brothers walk hand in hand

Tell me why, oh why, oh why can’t my dream come true

oh why

There must be peace and understanding sometime

Strong winds of promise that will blow away the doubt and fear

If I can dream of a warmer sun

Where hope keeps shining on everyone

Tell me why, oh why, oh why won’t that sun appear

We’re lost in a cloud

With too much rain

We’re trapped in a world

That’s troubled with pain

But as long as a man

Has the strength to dream

He can redeem his soul and fly

Deep in my heart there’s a trembling question

Still I am sure that the answer gonna come somehow

Out there in the dark, there’s a beckoning candle

And while I can think, while I can talk

While I can stand, while I can walk

While I can dream, please let my dream

Come true, right now

Let it come true right now

Oh yeah

![]() Songwriters: Earl Brown

Songwriters: Earl Brown

If I Can Dream lyrics © Raleigh Music Publishing

By Robert Morrison, Professor of English Language and Literature, Queen’s University, Ontario

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.