By Jennifer MacCormack, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Have you ever been grumpy, only to realize that you’re hungry?

Many people feel more irritable, annoyed, or negative when hungry – an experience colloquially called being “hangry.” The idea that hunger affects our feelings and behaviors is widespread – from advertisements to memes and merchandise. But surprisingly little research investigates how feeling hungry transforms into feeling hangry.

Psychologists have traditionally thought of hunger and emotions as separate, with hunger and other physical states as basic drives with different physiological and neural underpinnings from emotions. But growing scientific evidence suggests that your physical states can shape your emotions and cognition in surprising ways.

Prior studies show that hunger itself can influence mood, likely because it activates many of the same bodily systems, like the autonomic nervous system and hormones, that are involved in emotion. For example, when you’re hungry, your body releases a host of hormones including cortisol and adrenaline, often associated with stress. The result is that hunger, especially at greater intensity, can make you feel more tense, unpleasant and primed for action – due to how these hormones make you feel.

But is feeling hangry just these hunger-induced feelings or is there more to it? This question inspired the studies that psychologist Kristen Lindquist and I conducted at UNC-Chapel Hill. We wanted to know whether hunger-induced feelings can transform how people experience their emotions and the world around them.

Negative situations set the scene for hanger

An idea in psychology known as affect-as-information theory holds that your mood can temporarily shape how you see the world. In this way, when you’re hungry, you may view things in a more negative light than when you’re not hungry. But here’s the twist.

People are most likely to be guided by their feelings when they’re not paying attention to them. This suggests that people may become hangry when they aren’t actively focused on their internal feelings, but instead wrapped up in the world around them, such as that terrible driver or that customer’s rude comment.

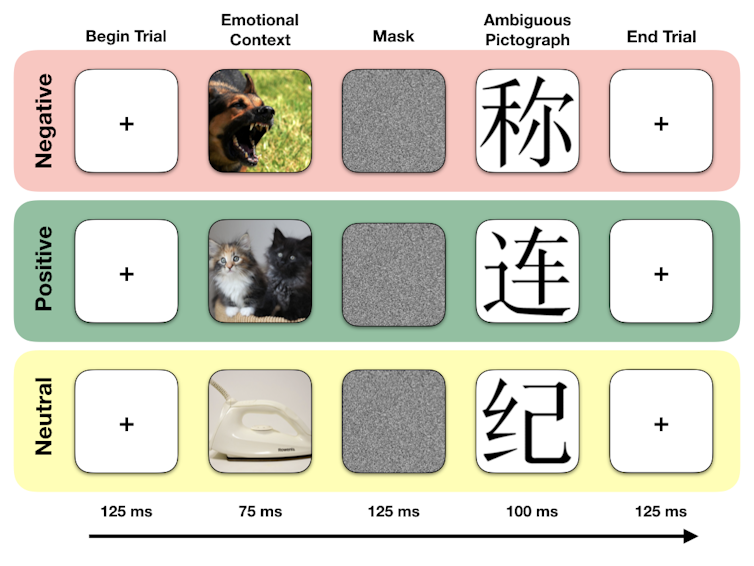

To test whether hungry people are more likely to become hangry in negative situations when they aren’t focused on their feelings, we designed three different studies. In the first two, run online with U.S. adults, we asked people – some hungry, some full – to look at negative, positive and neutral emotional images. Then they saw an ambiguous figure: a Chinese character or pictograph they’d never seen before. We asked participants whether they thought the pictograph meant something pleasant or unpleasant.

Jennifer MacCormack, CC BY-ND

Hungry people who saw negative images thought the pictographs meant something more unpleasant. However, hungry people’s ratings after positive or neutral emotional pictures were no different than the not-hungry people.

This suggests that the hangry bias doesn’t occur when people experience positive or even neutral situations. Instead, hunger only becomes relevant when people confront negative stimuli or situations. But why would hunger only matter in negative situations?

Affect-as-information theory also suggests that people are more likely to use their feelings as information about the world around them when those feelings match the situation they’re in. Hunger likely only becomes relevant in negative situations because hunger itself produces unpleasant feelings – making it easier to mistake the cause of those feelings to be the negative things around you, rather than your hunger.

Tuning in to your feelings

In the final study, we recreated in the laboratory a frustrating situation to test how hunger and awareness – or lack thereof – might cause hanger.

We assigned two random groups of undergraduate students to fast for at least five hours or eat a full meal before coming to our lab. There we assigned them to write a story that was meant either to direct their attention to emotional information, or to not focus on emotions at all. Then everyone did a long, tedious computer task. At the end of the task, we secretly programmed the computer to “crash.” The researcher blamed the participant for the computer malfunction and told them they’d have to redo the task once it was fixed.

It turned out that hungry people who hadn’t focused on feelings beforehand exhibited more signs of being hangry. They reported feeling more stressed, hateful and other negative emotions and rated the researcher as being more “judgmental,” compared to full individuals and the hungry people who did write about emotions earlier.

These findings suggest that feeling hangry occurs when your hunger-induced negativity gets blamed on the external world around you. You think that person who cut you off on the road is the one who made you angry – not the fact that you’re ravenous. This seems to be a fairly unconscious process: People don’t even realize they’re making these attributions.

Our data suggest that paying attention to feelings may short circuit the hangry bias – and even help reduce hanger once you notice it.

Ana Blazic Pavlovic/Shutterstock.com

Although these studies provide a valuable glimpse into the ways that physical states, like hunger, can temporarily shape our feelings and behaviors, they are only a first step. For example, our studies only address hunger effects in healthy populations where individuals eat regularly. It would be interesting to look at how feeling hangry could change with long-term dieting or conditions like diabetes or eating disorders.

These studies alongside other emerging science suggest that our bodies can deeply shape how we think, feel and act – whether we realize it or not. We’re generally aware that emotions like feeling stressed can influence our health, but the reverse direction is also true. Our bodies and physical health have the power to shape our mental lives, coloring who we are and the way we experience the world around us.

Warding off hanger

Here are three pro tips to help keep your hunger from going full-blown hangry.

First, it may seem obvious, but pay more attention to your hunger. People vary a lot in how sensitive they are to hunger and other bodily cues. Maybe you don’t notice you’re hungry until you’re already ravenous. Plan ahead – carry healthy snacks, eat a protein-filled breakfast or lunch to give you lasting energy – and set yourself reminders to eat regularly. These basic precautions help prevent you from becoming overly hungry in the first place.

But what if you’re already super hungry and can’t eat right away? Our findings suggest people are more likely to be biased by hunger in negative situations. Maybe you’re stuck in bad traffic or you have a stressful deadline. In these cases, try to make your environment more pleasant. Listen to an amusing podcast while you drive. Put on pleasant music while you work. Do something to inject positivity into your experience.

![]() Most importantly, your awareness can make all the difference. Yes, maybe you’re hungry and starting to feel road rage, overwhelmed with your task deadline, or wounded by your partner’s words. But amid the heat of those feelings, if you can, step back for a moment and notice your growling stomach. This could help you recognize that hunger is part of why you feel particularly upset. This awareness then gives you the power to still be you, even when you’re hungry.

Most importantly, your awareness can make all the difference. Yes, maybe you’re hungry and starting to feel road rage, overwhelmed with your task deadline, or wounded by your partner’s words. But amid the heat of those feelings, if you can, step back for a moment and notice your growling stomach. This could help you recognize that hunger is part of why you feel particularly upset. This awareness then gives you the power to still be you, even when you’re hungry.

Jennifer MacCormack, Ph.D. Student in Psychology and Neuroscience, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.