“Cancer survivor” has become a catch-all phrase to refer to living individuals diagnosed with cancer at some point in their lives. Cancer clinics and clinicians, patient advocacy organizations and media reports commonly use the term.

Using cancer survivor as a descriptor is certainly an act with good intentions. After all, people diagnosed with cancer have a diverse array of physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs – and the language of survival can be empowering to many of them. For this reason, institutions that focus on cancer have framed the term broadly. For example, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship has defined cancer survivor as “any person diagnosed with cancer from the time of initial diagnosis until his or her death.”

Nevertheless, as marketing professors who study how to better serve patients, we were struck by the notion of applying the term “cancer survivor” so broadly that it would even include people who ultimately die of cancer.

Should the same term be used for the entire spectrum of living people who have experienced cancer, which represents more than 100 distinct diseases affecting approximately 14 million people in the United States?

A complex issue

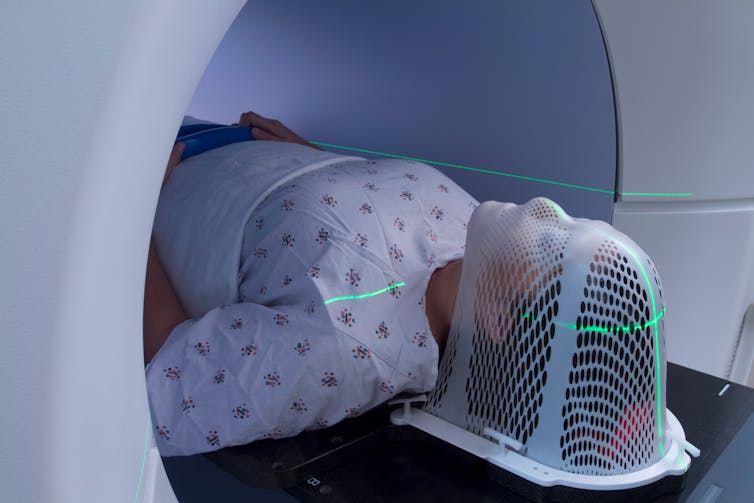

Mark_Kostich/Shutterstock.com

Indeed, the published research on this question reflects its complexity. An analysis of 23 studies of how people diagnosed with cancer view the term “cancer survivor” shows that although many embrace it, others see it as inappropriate. Some of them fear not surviving if cancer recurs; others think the term itself is disrespectful to people who die of cancer or believe the term better fits people with cancers more serious than their own.

Still others simply don’t want to live with the “survivor label” or don’t think the term reflects who they are. In studies that ask patients to make a discrete yes–no choice about whether they identify as a cancer survivor, the percentage who say “yes” ranges from about 31 percent to 78 percent, depending on the type of cancer and other individual factors, with breast cancer patients generally showing greater affinity for the term than patients with other types of cancer.

Recognizing that forcing a yes–no choice on this delicate question is not ideal, we partnered with Dr. Katie Deming, a radiation oncologist at Kaiser Permanente, and Dr. Jeffrey Landercasper, clinical adjunct professor of surgery at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, to conduct our own study of how current and former patients perceive the term “cancer survivor.” We measured reactions to the term in three ways: a seven-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, a 100-point allocation exercise from 0 (negative) to 100 (positive) on a continuous scale, and an open-ended question, “What is your personal opinion about the phrase ‘cancer survivor’ and why do you feel as you do?” We analyzed more than 1,400 surveys completed by patients, primarily with breast cancer, who belong to the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation’s Army of Women, an organization that connects researchers with people who want to participate in breast cancer research. About three-quarters of our respondents were currently undergoing cancer treatment.

Our findings reinforce the concern that motivated our study. Respondents’ average scores for the two quantitative questions were slightly above the scale midpoints, indicating many people are negatively disposed to the term. The open-ended question was especially revealing in documenting not only how respondents regarded the term but also why. Overall, about 60 percent of comments were negative, 29 percent positive, and 11 percent neutral.

Among the negative responses to the term “cancer survivor,” the most common theme had to do with its disregarding the patient’s fear of recurrence. One woman’s response captures the essence of this concern: “I feel like I’m tempting fate when I say I’ve survived it.”

Other women who felt negatively about the phrase made statements such as “I don’t deserve to carry the title proudly because I didn’t ‘suffer’ enough to earn [it]”; “I prefer not to define myself by my cancer diagnosis or status”; and “it erases the experience of those who [still] have or will die of the disease.”

Patients who felt positively about being called a cancer survivor often said they took pride in the accomplishment of surviving cancer – as one woman put it, “of winning the battle against this life-threatening disease.” Another said the term made her feel “empowered, instead of victimized.” Others cited the sense of community conferred by the phrase, specifically a “personal connection to other cancer patients.”

Our statistical analysis comparing respondents with negative perceptions versus positive perceptions of the term indicates that undergoing active cancer treatment, advanced cancer stage, and older age at diagnosis or study participation are associated with less positive perceptions.

Health care language should do no harm

Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock.com

The key takeaway from our study, and from other published research on the topic, is that using a single label to describe a diverse population of cancer patients in blanket fashion inevitably leaves a substantial percentage of them feeling unrepresented, perhaps even alienated, by the term – even though many others derive positive benefits from using and hearing it. In short, because the group of people typically described by the term is far from a monolith, a single phrase that is subjective rather than factual is unlikely to be up to the task. The label “cancer survivor” is not based on any specific fact related to a person’s particular treatment or diagnosis; it is plainly subjective.

Language used with and about patients is important and can cause needless distress when used without care. Why not let patients choose the language of their cancer-related identity so that it best reflects their own individual experiences and preferences? Existing research, including our own, suggests that the question is worth considering.![]()

By Leonard L. Berry, University Distinguished Professor of Marketing, Mays Business School; Senior Fellow, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Texas A&M University ; Andrea Flynn, Associate professor of Marketing, University of San Diego, and Scott Davis, Assistant professor of Marketing, University of Houston-Downtown

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.