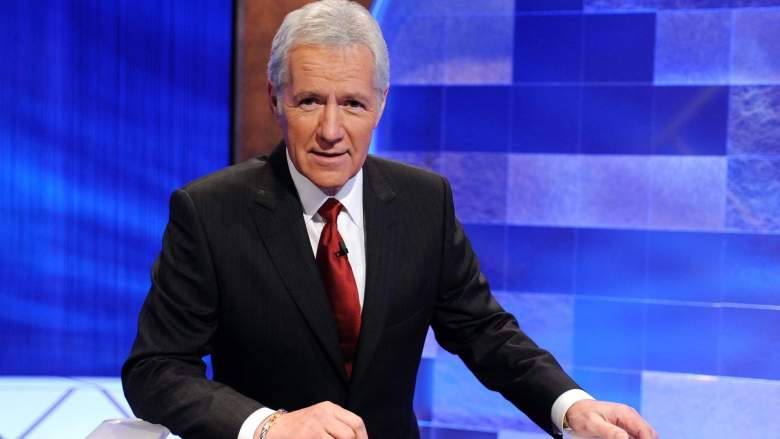

When “Jeopardy!” episode 7059 aired on April 30, 2015, the category was “The Human Body,” the price was $2,000, and the clue was “This gland’s main duct, the duct of Wirsung, collects its juices & empties into the duodenum.”

The question was “What is the pancreas?” Unbeknownst to Alex Trebek, the show’s beloved host, the cells that line the duct of his pancreas would develop into pancreatic cancer, or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Trebek announced on March 6, 2019 that he has pancreatic cancer, but that he will fight the disease and keep hosting the show. And in fact, he was back at work March 12.

“Truth told, I have to because under the terms of my contract, I have to host ‘Jeopardy’ for three more years,” he said jokingly. “So help me. Keep the faith, and we’ll win. We’ll get it done.”

I am a surgical and molecular pathologist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and routinely evaluate patients with pancreatic cancer. As a pathologist, I establish the diagnosis and evaluate the genetics of pancreatic cancer to improve early detection and treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Although Trebek’s recovery is still unknown, researchers are trying to develop diagnostic tests that will let people know earlier that they have this form of cancer. A study my colleagues and I recently published identified genetic differences in patients that might make current chemotherapies more effective.

Hard to Detect, Hard to Treat

Each day in the U. S., an estimated 155 Americans will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and an estimated 125 Americans will die of pancreatic cancer. About 55,440 will be diagnosed this year.

Within the first year of diagnosis, 74 percent of patients with pancreatic cancer will die from this dismal disease and 90 percent of patients will die within five years of their diagnosis.

What makes pancreatic cancer so deadly is that it is often found late in its disease course, as in the case of Trebek. Hence, time is of the essence when it comes to treatment.

Current options for most patients are chemotherapy, radiation and, for a minority, surgery. But every pancreatic cancer is different, and therefore it requires a personalized approach, such as understanding the different genetic changes occurring in each patient’s pancreatic cancer.

At the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), we try to genetically profile every patient with pancreatic cancer to define their best course of treatment. While pancreatic cancer is so dire, there are genetic changes that can be targeted with currently available medications, and it’s important to identify them sooner than later.

But, in order for us to accomplish this, we have to know what genomic changes to look for in pancreatic cancer. Hence, in collaboration with Foundation Medicine, my research team and I genetically profiled 3,594 patients from all over the world. We were looking for genetic changes that are linked to known therapeutic regimens for not only pancreatic cancer, but all cancer types. This approach has had some success with other cancer types. For example, a genetic mutation was found in some types of lung cancer that was sensitive to immunotherapy drugs such as Keytruda. That drug had first gained FDA approval for treatment of melanoma.

With such a large and diverse patient population, it is not surprising that there were a number of key findings from our study.

Mutations That Could Be Targeted

First, we found that 17 percent of pancreatic cancers contained genetic mutations that may be susceptible to currently available anti-cancer therapy. While many of the genetic mutations we detected in pancreatic cancer have been described previously, we also identified genetic changes that were reported in other cancer types, but never described in pancreatic cancer. Moreover, these mutations are known to be targetable with existing drug regimens and are potentially therapeutic for patients with pancreatic cancer as well.

Second, we discovered a significant number of pancreatic cancer patients harbored mutations in their germline DNA, or in other words, a genetic change that has been incorporated into every cell in their body.

Previous studies have shown that 10 percent of patients with pancreatic cancer report a family history of the disease, and a subset have been linked to specific genomic alterations. For example, germline alterations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are known to be associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, have also been linked to pancreatic cancer.

We were not surprised that these genes were frequently mutated among patients within our study and additional genes related to them were also found to be altered. This information paves the way for improved germline testing for patients that may have a history of pancreatic cancer with implications for their loved ones.

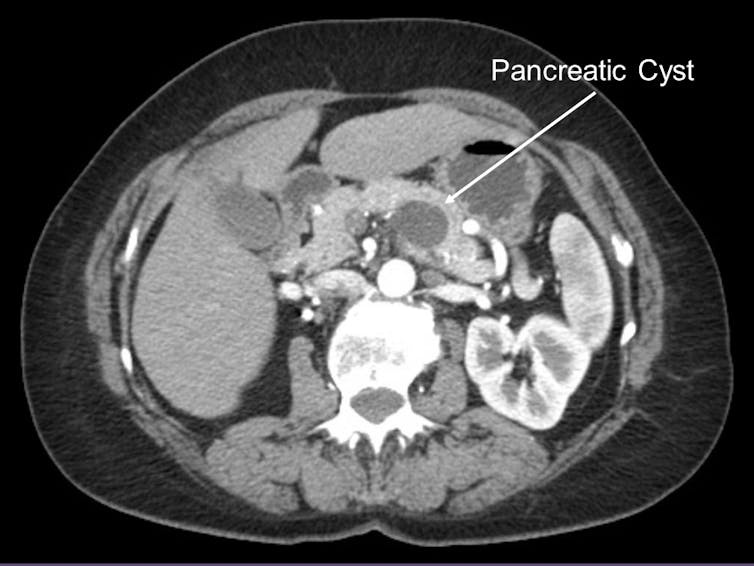

Our last bit of insight came from looking at the genomic changes in pancreatic cyst fluid. About 15 percent of pancreatic cancers are known to arise from pancreatic cysts, or fluid collections within the pancreas. Pancreatic cysts are often identified on routine abdominal imaging and, therefore, amenable to early detection. Because early detection of pancreatic cancer is an important cornerstone to improving patient survival, my team examined those pancreatic cancers arising from pancreatic cysts.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, CC BY-SA

Pancreatic cysts, however, are very common in the U.S. population. In fact, 1 to 2 percent of Americans who undergo an abdominal scan are found to have a pancreatic cyst. Certainly, not all pancreatic cysts will progress to pancreatic cancer and, therefore, tests to detect a pancreatic cancer arising within a pancreatic cyst early is needed.

In 2017, our team at UPMC reported the creation and validation of a clinically available test to evaluate patients with pancreatic cysts called PancreaSeq. PancreaSeq evaluates the genetic changes in pancreatic cyst fluid to identify those cysts that are likely to transform into pancreatic cancer. It is used by several institutions throughout the U.S.

Among the 3,594 pancreatic cancers profiled for our recent study, we identified key genetic alterations among pancreatic cancers arising from pancreatic cysts that could be incorporated into PancreaSeq and improve its ability to detect pancreatic cancer early.

We believe that our study provides a compendium of known genetic alterations for pancreatic cancer that may serve as a clinical resource to not only guide future treatment for patients undergoing targeted genetic profiling, but familial pancreatic cancer testing and early detection.![]()

By Aatur Singhi, Professor of Anatomy and Pathology, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.