Fears are growing that the new coronavirus will infect the U.S. economy.

U.S stocks are headed for their worst week since the 2008 financial crisis; companies including Apple and Walmart have been warning of potential sales losses from COVID-19 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention told Americans to prepare for the outbreak to spread to the United States, with unknown but potentially “bad” consequences.

Lately, many people have asked me, as an economist, a question I haven’t heard in years: Could a virus really send the global and U.S. economies into recession – or worse? Put more pertinently, will COVID-19 trigger an economic meltdown?

Underwood Archives/Getty Images

What a Virus Can Do

The worry is understandable; viruses are scary things. I’ve read my share of medical thrillers based on some new virus spreading throughout the globe killing millions, destroying businesses and almost ending civilization until heroes – super or not – contain it at the last minute.

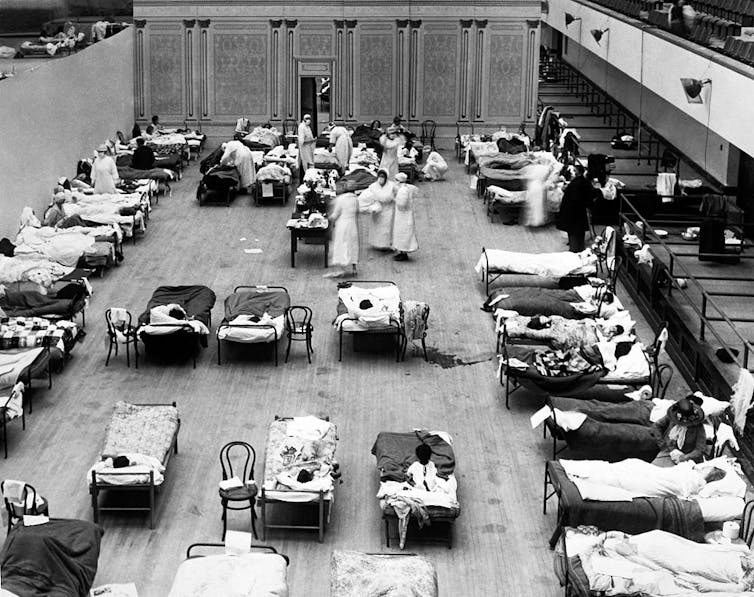

While these are works of fiction, we only have to look back 100 years to find a real example of what an unchecked virus can do.

The 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, also known as the Spanish flu, killed at least 50 million people worldwide, with some estimates putting the number as high as 100 million. In the U.S., almost 1 of every 3 people became infected, and 500,000 died. Even for those who survived, there were numerous cases of long-term physical disability.

Fortunately, the adverse economic impacts were short-lived. With today’s more mobile and interconnected world, however, some suggest any large-scale pandemic would be much more severe, with costs in the trillions.

To date, deaths from the coronavirus have been very small, totaling a little over 2,700 worldwide, out of more than 80,000 known cases – or only about 3.4%. Almost all of the deaths have been in China, where the virus was first detected. Rapid actions to quarantine infected individuals have likely limited the spread.

Yet even if the death rates are relatively low, the economy can still suffer. These economic impacts would likely come in four forms: shortages of products from China, reduced sales to China, a drop in consumer spending based on fears about the virus and falling stock prices.

Let me evaluate the potential impact of each, but bear in mind that they are all interconnected, and a drop in just one can affect the others.

Product Shortages

The U.S. imports over US$500 billion of products each year from China, everything from smartphones and televisions to clothing and machine parts. Sick people in China can’t work, which means they can’t make products. Closing off parts of the country from other areas also curtails production.

The reduced availability of Chinese products could slow some segments of the U.S. economy, with the computer and electronics industries being the most vulnerable. For example, many smartphones sold in the U.S. are assembled in China. Although U.S. retailers have some inventory, shortages will likely appear if the pandemic persists.

Americans are already beginning to see some impacts: for example, in shortages of dozens of drugs and other medical products and longer wait times for a variety of products such as bicycles and board games.

It’s too early to say how severe it will get, but the dependency of U.S. supply chains on China is a major concern. It shows how something like the coronavirus could become a huge problem in the modern economy.

Sales May Take a Hit

On the flip side, U.S. companies sell well over $100 billion of products to China annually, with the most important being technology like computer chips and agricultural products such as soybeans.

These sectors have already taken a hit from the tariffs imposed by China during the U.S.-China trade war of the last two years. The recent thaw in the conflict – and a limited deal with China – had created optimism for U.S. factories and farms that increased sales were around the corner.

That corner may be harder to reach as a result of the coronavirus outbreak and its significant impact on the Chinese economy. More U.S. companies are now worrying about their sales to China as a result.

Consumers Still Spending

Ultimately, more than anything, the spending of consumers drives the U.S. economy, accounting for roughly 70% of growth. Economists, policymakers and traders will be closely watching measures of this to help them understand how worried they should be.

Significant declines in spending are usually the most direct cause of a recession and often signal falling incomes and higher unemployment. But consumers also reduce spending as a result of fear – such as when they see traders panicking on Wall Street. That is, nothing actually bad has to happen to reduce spending, and this fear-induced penny pinching can have real-world consequences and even trigger a recession.

We saw this happen with the SARS virus in 2003, which resulted in 700 deaths worldwide. Consumer confidence about the future dipped, and so did spending, especially on durable products like appliances, vehicles and furniture. Fortunately, the dip was short-lived, and no recession resulted.

Although coronavirus-related deaths already exceed those from SARS, consumer confidence has not yet been affected. The latest data, released on Feb. 25, shows it continued to rise in February, albeit at a slower-than-expected pace and based on a survey taken before the recent stock market swoon. And measures of consumer spending like retail sales are also still growing, if at a subdued rate.

Also, there could be two positive offsets from the virus that will boost consumers. One is a reduction in interest rates that has already occurred and will be welcome news for people borrowing money for a home or vehicle. Second is a drop in oil – and, ultimately, gas – prices that will mean less money to be paid at the pump.

So it appears, for now, that consumers are more focused on jobs, incomes and gas prices than on COVID-19.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

A Rocky Road for Stocks

Lastly, let’s look at the impact on stocks.

One thing traders and investors absolutely do not like is uncertainty. And that’s what we have right now: No one, not even me, knows how bad the outbreak will get or what the impact will be on companies, consumers and the economy.

Until we have a good idea of how much the virus will spread and whether containment efforts will be successful, markets could remain wobbly. The Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index has plunged more than 10% since Feb. 21, ending a bull market that lasted 12 years.

A falling stock market could affect the real economy in a number of ways, including by sapping consumer confidence and reducing their spending.

But just as a bout of bad news can send markets into a tailspin, a reason for optimism could cause a rebound just as fast.

Brace for impact – and uncertainty

For now, we’ll all – traders, companies, consumers – have to just live with uncertainty, not knowing just how bad it will get.

The best all of us can do is monitor the situation and take precautions to prevent its spread – and be ready if it does.

A key measure to watch is the trend in the number of new cases reported worldwide. A reduction is often a sign the virus is running its course. However, a jump in cases could be cause for alarm, especially if the increase is large.

Companies and industries in the U.S. having strong ties to China or other countries with major infections could be in for a rocky road ahead, but with any luck the challenges will last weeks or months – not years. As long as U.S. consumers continue to spend, the economy will continue to expand, and there’s little risk of recession. If the stock market tumbles further, however, all bets may be off.

This article has been updated from the original version published Feb. 26.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]![]()

Michael Walden, Professor and Extension Economist, North Carolina State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.