Apollo 1 was destined to be a major step in humanity’s reach toward the moon, but it became one of space flight’s biggest tragedies weeks before it was scheduled to leave the launch pad. The Apollo 1 crew died in a flash fire in Cape Canaveral, Florida, January 27, 1967.

The Manned Spaceflight Center in Houston, now known as the NASA Johnson Space Center and Mission Control Center, monitored all of Apollo’s lunar missions. The Apollo program began in 1963 with the goal of landing humans on the moon and returning them safely back to Earth, according to The NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Its first manned mission, Apollo 1, originally called AS-204, was designed as a suborbital test of the new command module.

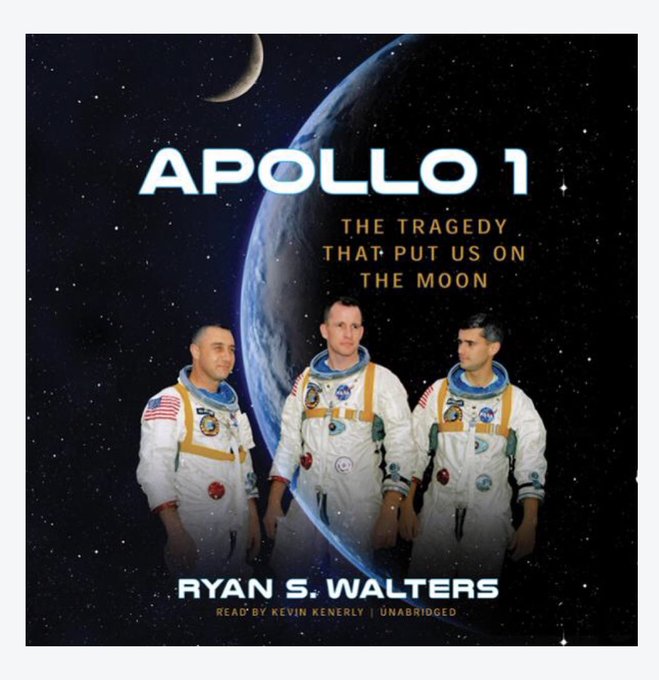

The program was halted after the deaths of the three astronauts, Commander Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Command Pilot Edward White, and Pilot Roger Chaffee.

Follow the Heavy on Houston Facebook page for the latest Houston news and more.

Here’s what you need to know:

A Short Circuit & Spark Caused a Fast-Moving Blaze That Killed the Apollo 1 Crew in About 30 Seconds

The preflight test that killed the Apollo 1 crew was not expected to be dangerous, according to The NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Apollo 1 was designated as the first manned launch in the Apollo program, an Earth-orbiting mission that was scheduled to launch February 21, 1967.

On January 27, 1967, Grissom, White and Chaffee stepped into the Apollo Command Module for a “plugs out” test on the Saturn 1B launch pad at Cape Canaveral. The command module was not fueled. The test involved a countdown of the entire flight sequence, NASA writes.

The NASA archive says:

At 1 p.m. on Friday, 27 January 1967 the astronauts entered the capsule on Pad 34 to begin the test. A number of minor problems cropped up which delayed the test considerably and finally a failure in communications forced a hold in the count at 5:40 p.m. At 6:30 p.m., Grissom said “How are we going to get to the Moon if we can’t talk between three buildings?” At 6:31 p.m. a surge was recorded in the AC bus 2 voltage readings, possibly indicating a short-circuit. The cockpit recording is difficult to interpret in places but a few seconds later one of the astronauts (probably Chaffee) is heard to say what sounds like “Flames!”. Two seconds after that White was heard to say, “We’ve got a fire in the cockpit.” The fire spread throughout the cabin in a matter of seconds. Chaffee said, “We have a bad fire!”, followed by shouting. The last crew communication ended 17 seconds after the first indication of the start of the fire, followed by loss of all telemetry. The Apollo hatch could only open inward and was held closed by a number of latches which had to be operated by ratchets. It was also held closed by the interior pressure, which was higher than outside atmospheric pressure and required venting of the command module before the hatch could be opened. It took at least 90 seconds to get the hatch open under ideal conditions. Because the cabin had been filled with a pure oxygen atmosphere at normal pressure for the test and there had been many hours for the oxygen to permeate all the material in the cabin, the fire spread rapidly and the astronauts had no chance to get the hatch open. Nearby technicians tried to get to the hatch but were repeatedly driven back by the heat and smoke. By the time they succeeded in getting the hatch open roughly 5 minutes after the fire started the astronauts had already perished, probably within the first 30 seconds, due to smoke inhalation and burns.

An investigation concluded that the blaze likely started with a short circuit from a bundle of wires that ran near Grissom’s seat, NASA writes. The pure oxygen caused the fire to spread quickly and rapidly, and the hatch design left the crew trapped inside the inferno.

The Apollo Program Took a 20-Month Hiatus for Investigation & Redesign

The Apollo 204 Senate Report, published January 30, 1968, said that no single person could be blamed for the tragedy.

“It happened because many people made the mistake of failing to recognize a hazardous situation,” the report says.

The report goes on to honor the lives of the men, but says that the program must continue in recognition of their sacrifice – while paying close attention to the lessons learned.

“Three courageous men lost their lives in this tragic accident,” the report says. “They died in the service of their country. Because of their deaths, manned spaceflight will be safer for those who follow them. The names Grissom, White and Chaffee are recorded in history and the most fitting memorial this country can leave these men is the success of the Apollo program–the goal for which they gave their lives.”

The NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive elaborated on the redesign, writing:

A number of changes were instigated in the program over the next year and a half, including designing a new hatch which opened outward and could be operated quickly, removing much of the flammable material and replacing it with self-extinguishing components, using a nitrogen-oxygen mixture at launch, and recording all changes and overseeing all modifications to the spacecraft design more rigorously.

The mission, originally designated Apollo 204 but commonly referred to as Apollo 1, was officially assigned the name “Apollo 1” in honor of Grissom, White, and Chaffee. The first Saturn V launch (uncrewed) in November 1967 was designated Apollo 4 (no missions were ever designated Apollo 2 or 3). The Apollo 1 Command Module capsule 012 was impounded and studied after the accident and was then locked away in a storage facility at NASA Langley Research Center. The changes made to the Apollo Command Module as a result of the tragedy resulted in a highly reliable craft which, with the exception of Apollo 13, helped make the complex and dangerous trip to the Moon almost commonplace. The eventual success of the Apollo program is a tribute to Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee, three fine astronauts whose tragic loss was not in vain.

NASA Flight Director Gene Kranz was more blunt with his words, according to the Houston Chronicle, which covered the Apollo program extensively for the 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s walk on the moon.

“Somewhere, somehow, we screwed up,” Kranz told his team after the disaster, according to the Houston Chronicle. “We were too gung-ho about the schedule and we locked out all the problems we saw each day in our work … We were not ready. We did not do our job.”

Extensive work continued during the hiatus, the Houston Chronicle reported, and included a redesign of the command and service module.

“From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: tough and competent,” Kranz said at the time, according to the feature. “Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or fail to do. Competent means we will never take anything for granted.”

Comments

This Month in Houston History: Apollo 1 Crew Dies in Fire January 27, 1967