When winter cold settles in across the U.S., the alleged “War on Christmas” heats up.

In recent years, department store greeters and Starbucks cups have sparked furor by wishing customers “happy holidays.” This year, with state officials warning of holiday gatherings becoming superspreader events in the midst of a pandemic, opponents of some public health measures to limit the spread of the pandemic are already casting them as attacks on the Christian holiday.

But debates about celebrating Christmas go back to the 17th century. The Puritans, it turns out, were not too keen on the holiday. They first discouraged Yuletide festivities and later outright banned them.

At first glance, banning Christmas celebrations might seem like a natural extension of a stereotype of the Puritans as joyless and humorless that persists to this day.

But as a scholar who has written about the Puritans, I see their hostility toward holiday gaiety as less about their alleged asceticism and more about their desire to impose their will on the people of New England – Natives and immigrants alike.

An Aversion to Christmas Chaos

The earliest documentary evidence for their aversion to celebrating Christmas dates back to 1621, when Gov. William Bradford of Plymouth Colony castigated some of the newcomers who chose to take the day off rather than work.

But why?

As a devout Protestant, Bradford did not dispute the divinity of Jesus Christ. Indeed, Puritans spent a great deal of time investigating their own and others’ souls because they were so committed to creating a godly community.

Bradford’s comments reflected Puritans’ lingering anxiety about the ways that Christmas had been celebrated in England. For generations, the holiday had been an occasion for riotous, sometimes violent behavior. The moralist pamphleteer Phillip Stubbes believed that Christmastime celebrations gave celebrants license “to do what they lust, and to folow what vanitie they will.” He complained about rampant “fooleries” like playing dice and cards and wearing masks.

Civil authorities had mostly accepted the practices because they understood that allowing some of the disenfranchised to blow off steam on a few days of the year tended to preserve an unequal social order. Let the poor think they are in control for a day or two, the logic went, and the rest of the year they will tend to their work without causing trouble.

English Puritans objected to accepting such practices because they feared any sign of disorder. They believed in predestination, which led them to search their own and others’ behavior for signs of saving grace. They could not tolerate public scandal, especially when attached to a religious moment.

Puritan efforts to crack down on Christmas revelries in England before 1620 had little impact. But once in North America, these seekers of religious freedom had control over the governments of New Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut.

Puritan Intolerance

Boston became the focal point of Puritan efforts to create a society where church and state reinforced each other.

The Puritans in Plymouth and Massachusetts used their authority to punish or banish those who did not share their views. For example, they exiled an Anglican lawyer named Thomas Morton who rejected Puritan theology, befriended local Indigenous people, danced around a maypole and sold guns to the Natives. He was, Bradford wrote, “the Lord of Misrule” – the archetype of a dangerous type who Puritans believed create mayhem, including at Christmas.

In the years that followed, the Puritans exiled others who disagreed with their religious views, including Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams who espoused beliefs deemed unacceptable by local church leaders. In 1659, they banished three Quakers who had arrived in 1656. When two of them, William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson, refused to leave, Massachusetts authorities executed them in Boston.

This was the context for which Massachusetts authorities outlawed Christmas celebrations in 1659. Even after the statute left the law books in 1681 during a reorganization of the colony, prominent theologians still despised holiday festivities.

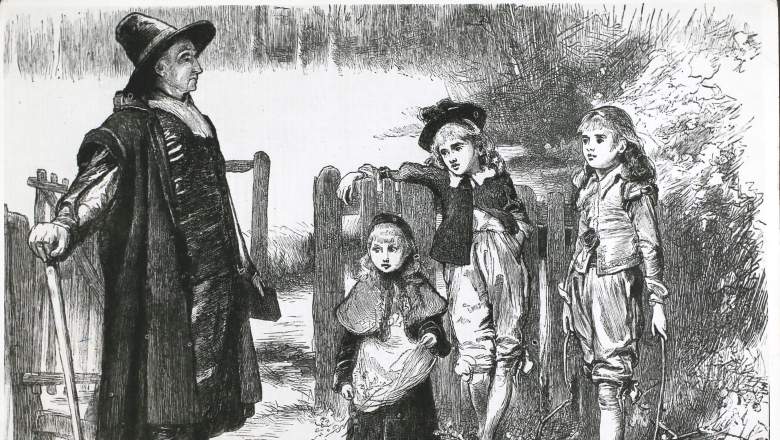

Stock Montage via Getty Images

In 1687, the minister Increase Mather, who believed that Christmas celebrations derived from the bacchanalian excesses of the Roman holiday Saturnalia, decried those consumed “in Revellings, in excess of wine, in mad mirth.”

The hostility of Puritan clerics to celebrations of Christmas should not be seen as evidence that they always hoped to stop joyous behavior. In 1673, Mather had called alcohol “a good creature of God” and had no objection to moderate drinking. Nor did Puritans have a negative view of sex.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

What the Puritans did want was a society dominated by their views. This made them eager to convert Natives to Christianity, which they managed to do in some places. They tried to quash what they saw as usurious business practices within their community, and in Plymouth they executed a teenager who had sex with animals, the punishment prescribed by the Book of Leviticus. When the Puritans believed that Indigenous people might attack them or undermine their economy, they lashed out – most notoriously in 1637, when they set a Pequot village on fire, murdered those who tried to flee and sold captives into slavery.

By comparison to their treatment of Natives and fellow colonists who rebuffed their unbending vision, the Puritan campaign against Christmas seems tame. But it is a reminder of what can happen when the self-righteous control the levers of power in a society and seek to mold a world in their image.![]()

By Peter C. Mancall, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.