Zitkala-Sa was a Yankton Dakota Sioux writer, translator, musician, educator and political activist who is being celebrated with a Google Doodle on her 145th birthday. She was also known by the name Gertrude Simmons Bonnin.

Google said the Doodle, “celebrates the 145th birthday of writer, musician, teacher, composer, and suffragist Zitkala-Ša, a member of the Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota (Ihanktonwan Dakota Oyate or ‘People of the End Village’). A woman who lived resiliently during a time when the Indigenous people of the United States were not considered real people by the American government, let alone citizens, Zitkala-Ša devoted her life to the protection and celebration of her Indigenous heritage through the arts and activism.”

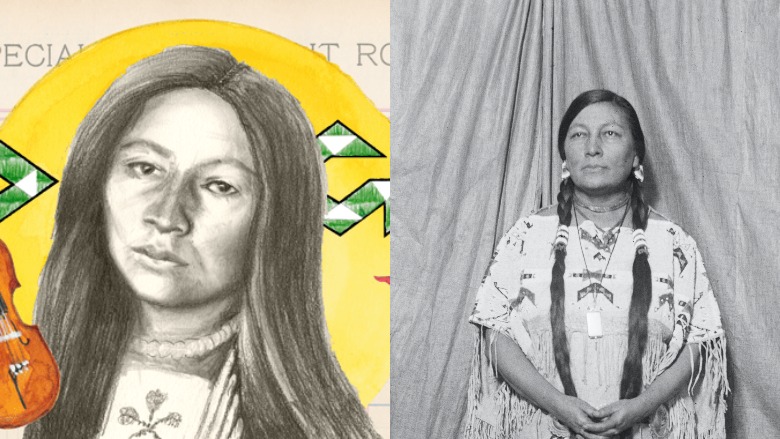

According to Google, the Doodle is designed by Chris Pappan, an “American Indian guest artist of Osage, Kaw, Cheyenne River Sioux, and European heritage.” Google added, “Happy Birthday, Zitkala-Ša, and thank you for your efforts to protect and celebrate Indigenous culture for generations to come.”

Here’s what you need to know about Zitkala-Sa:

1. Zitkala-Sa Was Born on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota & Her Name Translates From the Lakota/Lakȟótiyapi to ‘Red Bird’

Zitkala-Sa was born on February 22, 1876, on the Yankton Indiana Reservation in South Dakota, according to the National Park Service. According to her biography on the NPS website, Zitkala-Sa translates to “Red Bird” in the Lakota/Lakȟótiyapi, which was spoken by her tribe, the Yankton Dakota Sioux. She was raised by a single mother after her father left the family, according to the biography.

According to the New York Historical Society, “little is known about her father, who was Anglo-American.”

In her work, Zitkala-Sa. Impressions of an Indian Childhood, she wrote about her childhood on the reservation and with her mother. In one story, she wrote about watching her mother to learn beadwork and how to make moccasins and other items, and imitating her by trading the items with her friends.

“I remember well how we used to exchange our necklaces, beaded belts, and sometimes even our moccasins. We pretended to offer them as gifts to one another. We delighted in impersonating our own mothers,” she wrote in the chapter titled The Beadwork. “We talked of things we had heard them say in their conversations. We imitated their various manners, even to the inflection of their voices. In the lap of the prairie we seated ourselves upon our feet; and leaning our painted cheeks in the palms of our hands, we rested our elbows on our knees, and bent forward as old women were most accustomed to do.”

2. She Was Sent to a Boarding School When She Was 8, Where Her Hair Was Forcibly Cut & She Was Forbidden From Speaking Her Native Language

According to the New York Museum of History, Zitkala-Sa was sent to a boarding school in Indiana when she was 8 after Quaker missionaries visited her reservation. It was there that she was given the name Gertrude Simmons. “She attended the Institute until 1887. She was conflicted about the experience, and wrote both of her great joy in learning to read and write and to play the violin, as well as her deep grief and pain of losing her heritage by being forced to pray as a Quaker and cut her hair,” the National Park Service wrote. The New York Historical Society wrote about her experiences:

For children who had never been off the reservation, the school sounded like a magical place. The missionaries told stories about riding trains and picking red apples in large fields. After debating the decision, Zitkala-Sa’s mother agreed to let her go. She did not want her daughter to leave and did not trust the white strangers, but she feared that the Dakota way of life was ending. There were no schools on the reservation, and she wanted her daughter to have an education.

According to her autobiography, as soon as Zitkala-Sa boarded the train, she regretted begging her mother to let her go. She was about to spend years away from everything she knew. She did not know English, and tribal languages were banned at the school. She would be forced to give up her Dakota culture for an ‘American’ one.

Zitkala-Sa’s arrival at the school was traumatic. The children learned that everyone would get a haircut. In Dakota culture, the only people to get haircuts were cowards who had been captured by the enemy. Zitkala-Sa resisted by hiding in an empty room. When the staff of the school found her underneath a bed, they dragged her out, tied her to a chair, and cut off her braids as she cried out loud. Later in life, she wrote that the staff at the school did not care about her feelings and treated the children like ‘little animals.’

In The Schooldays of an Indian Girl, she wrote she was “neither a wild Indian nor a tame one.” According to the Akta Lakota Museum & Cultural Center, “the estrangement from her mother and the old ways of the reservation had grown, as had her resentment over the treatment of American Indians by the state, church and population at large.”

After her time at the boarding school, Zitkala-Sa briefly returned to the reservation before she returned to Indiana, where she attended Earlham College in Richmond. She would go on to teach at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania and studied and performed at the Boston Conservatory of Music. Ziktala-Sa was a talented violinist and also wrote music.

Google wrote, “This was a common experience for thousands of Indigenous children in the wake of the Civilization Fund Act of 1819, which provided funding for missionaries and religious groups to create a system of Indian boarding schools that would forcibly assimilate Indigenous children. While she took interest in some of the experiences in her new environment, such as learning the violin, she resisted the institutional efforts to assimilate her into European American culture—actions she protested through a lifetime of writing and political activism.”

3. Zitkala-Sa Chronicled Native American Legends & History in Books & Wrote Articles for Publications Including the Atlantic Monthly & Harper’s Monthly

GettyAmong the prominent women who attended the meeting of the National Women’s Party in Washington was Mrs. Gertrude Bonnin, nee Princess Zitkala-Sa of the Sioux tribe.

Google wrote in its description of the Zitkala-Sa Doodle, “Returning back home to her reservation, Zitkala-Ša chronicled an anthology of oral Dakota stories published as Old Indian Legends in 1901. The book was among the first works to bring traditional Indigenous American stories to a wider audience. Zitkala-Ša was also a gifted musician. In 1913, she wrote the text and songs for the first Indigenous American opera, The Sun Dance, based on one of the most sacred Sioux ceremonies.”

Zitkala-Sa also wrote about Native experiences for several publications, including Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Monthly. She wrote in The Schooldays of an Indian Girl:

For the white man’s papers I had given up my faith in the Great Spirit. For these same papers I had forgotten the healing in trees and brooks. On account of my mother’s simple view of life, and my lack of any, I gave her up, also. I made no friends among the race of people I loathed. Like a slender tree, I had been uprooted from my mother, nature, and God. I was shorn of my branches, which had waved in sympathy and love for home and friends. The natural coat of bark which had protected my oversensitive nature was scraped off to the very quick.

The New York Historical Society wrote, “Zitkala-Sa channeled her frustration into a love for writing. She wrote about her personal experiences and the customs and values she had learned from her mother.”

4. Zitkala-Sa Co-Founded the National Council of American Indians to Lobby for U.S. Citizenship & Civil Rights for Native People

Gertrude Kasebier/Smithsonian InstitutionZitkala-Sa.

Zitkala-Sa also in 1926, according to PBS’ American Masters, “to lobby for increased political power for American Indians, and the preservation of American Indian heritage and traditions.”

According to American Masters, “Zitkála-Šá became increasingly involved in the struggle for American Indian rights, lobbying for U.S. citizenship, voting, and sovereignty rights. She was appointed the secretary of the Society of American Indians, the first national rights organization run by and for American Indians, and edited its publication American Indian Magazine.”

According to Google, “In addition to her creative achievements, Zitkala-Ša was a lifelong spokesperson for Indigenous and women’s rights. … Zitkala-Ša’s work was instrumental in the passage of historic legislation, such as the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924—granting citizenship to Indigenous peoples born in the United States—as well as the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.”

In 1920, she spoke about the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, telling Alice Paul’s National Women’s Party to remember their Native sisters, who were not given suffrage. According to The New York Times, she said in a speech, “The Indian woman rejoices with you.”

The Times wrote in a January 2020 article, she, “and other Native suffragists would continue to remind audiences that federal assimilation policy had attacked their communities and cultures. Despite treaty promises, the U.S. dismantled tribal governments, privatized tribally-held land and removed Native children to boarding schools. Those devastating policies resulted in massive land loss, poverty and poor health that reverberate through these communities today.”

5. Zitkala-Sa, Who Was Married & Had a Son, Died in 1938

Zitkala-Sa was married to Raymond Talesfase Bonnin, who she met while they were both working at the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, according to the New York Historical Society. They had one son, who was born in 1902 and was also named Raymond. She and her family spent time living in Utah, where she taught at a school on the Ute reservation, before relocating to Washington D.C. so they could increase their activism.

According to the New York Historical Society, “Throughout her life she actively opposed the “Americanization” of Native American culture, and her writing continued to have an impact on policymakers long after her death.” She died on January 26, 1938, in Washington D.C. She is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

In 2019, The Journey Museum and Learning Center paid tribute to Zitkala-Sa during Women’s History Month. Speaker Lily Mendoza told NewsCenter1, “We need to know who we are and where we come from, especially in our Native Community. And then to also educate Non-Natives in our community that there are strong women out there from the past that have worked for our rights. Not only for Native people, but non Native people as well.”

Mendoza said about Zitkala-Sa and her efforts to gain the right to vote for Natives, which was secured in 1924, “We weren’t registered to vote. And not being registered to vote really stops us from having any kind of a voice.”

READ NEXT: UCLA Student Charged in Capitol Riot