In his response to the August 17 attack in Barcelona, President Donald Trump told his followers to “Study what General Pershing of the United States did to terrorists when caught.” But the story he is referring to is a myth that never happened.

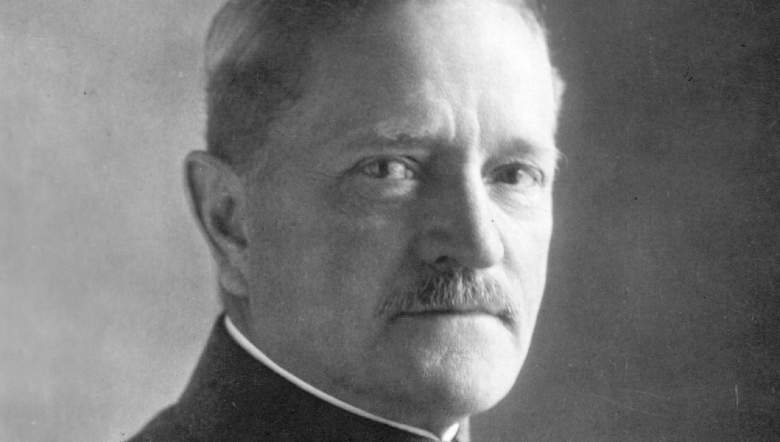

During the presidential campaign, Trump repeatedly referred to a story that General John J. Pershing executed Muslim prisoners in the Philippines during the early 1900s. Pershing, who is famous for leading the American Army forces in Europe during World War I, “caught 50 terrorists that did tremendous damage and killed many people and he took the 50 terrorists and he took 50 men and he dipped 50 bullets in pig’s blood,” as Trump said during one rally in 2016.

Trump continued, “And he had his men load his rifles, and he lined up the 50 people, and they shot 49 of those people. And the 50th person, he said: ‘You go back to your people, and you tell them what happened.'”

However, there is no evidence to back up this story.

Here’s a look at the myth that Pershing “dipped 50 bullets in pig’s blood” then executed Muslims.

1. The Story, as Trump Told it, Is False & There’s No Proof it Happened

Trump began telling the story in February 2016, while on the campaign trail, as an example of how to deal with “radical Islamic terrorists.” As The Washington Post notes, Trump told the story while he advocated for the return of waterboarding. This led to Trump telling a crowd in South Carolina a story about the “rough guy, rough guy” Pershing.

Trump said:

“They were having terrorism problems, just like we do… And he caught 50 terrorists who did tremendous damage and killed many people. And he took the 50 terrorists, and he took 50 men and he dipped 50 bullets in pigs’ blood — you heard that, right? He took 50 bullets, and he dipped them in pigs’ blood. And he had his men load his rifles, and he lined up the 50 people, and they shot 49 of those people. And the 50th person, he said: You go back to your people, and you tell them what happened. And for 25 years, there wasn’t a problem. Okay? Twenty-five years, there wasn’t a problem. By the way, this is something you can read in the history books — not a lot of history books because they don’t like teaching this.”

Trump didn’t say the word “Muslim” in the story, but he noted, “There’s a whole thing with swine and animals and pigs, and — you know the story, you know they don’t like that.” Eating pork is forbidden in Islam.

However, the story isn’t true. Snopes explains that it’s “false” and Politifact classified it as “Pants on Fire.”

2. The Story Has Its Roots in Pershing’s Tenure as Governor of the Philippines’ Moro Province After the Philippine-American War

The story has its roots in Pershing’s tenure as the Governor of the Moro Province in the Philippines, as Snopes explains. After the Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. took control of the Philippines until its independence in 1946. Between 1898 and 1945, the American military fought off independence movements. The Philippine-American War lasted from 1899 to 1902.

But while that war was over, the military continued fighting the Moro Rebellion until 1913. “Moro” is a term describing the ethnic Muslims who lived in the Moro Province. Pershing was the Governor of the province from 1909 to 1913.

Snopes points out that there is no evidence that Pershing specifically did what Trump said he did in Pershing biographies. There is an incident when Pershing’s order to ban firearms was ignored. This led to the Second Battle of Bud Dajo in 1911. Pershing wanted to avoid a repeat of the First Battle of Bud Dajo in 1906, which was a disaster. Almost 1,000 Moro people died and it became known as the “Bud Dajo Massacre.”

Pershing kept casualties in the battle limited. Twelve Moro fighters died in the Second Battle of Bud Dajo. However, the rebellion continued until 1913.

3. Pershing Wanted to Avoid Inspiring Religious Fanaticism, but There’s Evidence That 1 American Commander Threatened to Bury Muslims With a Pig

Pershing also wanted to avoid inspiring religious fanaticism. He had avoided turning the Second Battle of Bud Dajo into a massacre by negotiating with those assembled after his forces cut off their supply. He wrote that the Moro who had assembled to fight “were chagrined and disappointed in that they were not encouraged to die the death of Mohammedan fanatics.”

Pershing remained in the Philippines until 1913. After that, he took part in the Pancho Villa expedition, following the deaths of his three young daughters and wife from smoke inhalation.

During World War I, Pershing was made Commander of the American Expeditionary Force. After the war, he was made General of the Armies of the United States, the highest possible rank in the U.S. military. The position was created just for him. Pershing died in July 1948 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Politifact notes that a Pershing memoir titled My Life Before The World War, 1860-1917 includes a story of Col. Frank West. Pershing wrote that West had Muslim insurgents “publicly buried in the same grave with a dead pig. It was not pleasant to have to take such measures, but the prospect of going to hell instead of heaven sometimes deterred the would-be assassins.”

The editor of the new edition of My Life Before The War, John T. Greenwood, added that Maj. Gen. J. Franklin Bell wrote to Pershing that he thought it was a “good plan, for if anything will discourage the (insurgents) it is the prospect of going to hell instead of to heaven.” Bell also wrote that he endorsed the custom “to discourage crazy fanatics.”

The letters prove that the U.S. military did use pigs to threaten Muslim insurgents in the Philippines, but it doesn’t make Trump’s story true. There’s no evidence that Pershing oversaw this use of pigs. It also fails to prove his point that these practices dissuaded violence from Muslims for over a quarter-century.

“Where Trump’s remark becomes ridiculous is in the idea that this actually worked,” David J. Silbey, Cornell University historian, told Politifact. “The Moro War did not end until 1913, and even that’s a bit of a soft date, with violence continuing for quite a while afterward. Defilement by pig’s blood isn’t — and wasn’t — some magical method of ending terrorism.”

4. A Chicago Newspaper Report From 1927 Claimed Pershing Did Use Pig’s Blood, but Didn’t Shoot Blood-Dipped Bullets at Muslims

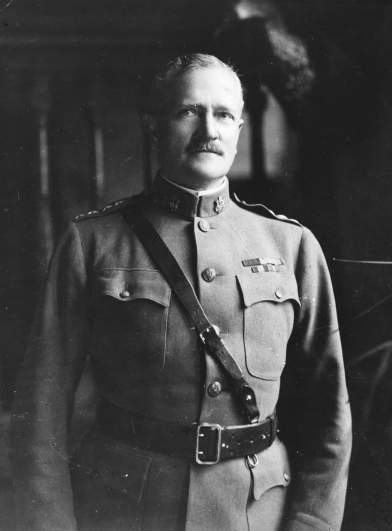

GettyPershing, who was nicknamed “Black Jack,” in 1918.

Author William Lambers wrote in February 2016 that there was a story about Pershing using pig’s blood, but it was published in a Chicago paper 14 years after Pershing left the Philippines. The story didn’t even involve Pershing firing blood-dipped bullets at the Moro rebels.

Lambers writes that the Chicago Daily Tribune reported in 1927 that Pershing sprinkled pig’s blood on Moro prisoners who thought it would condemn them for eternity. However, he didn’t kill them. He let them go with a warning that others would be sprinkled with pig’s blood as well. “Those drops of porcine gore proved more powerful than bullets,” the Tribune story read.

“If Pershing were around today he would be advocating food for the hungry child refugees, which are at unprecedented levels today because of the war in Syria,” Lambers wrote. “They never talk about hunger during the presidential debates, but it’s a top foreign policy issue, which Pershing and other great leaders have understood. Pershing was also deeply concerned about high levels of military spending. He often spoke about achieving global arms reductions and disarmament. Nations could work together to achieve this noble goal.”

Then, as Snopes found, there is a story from the 1938 book Jungle Patrol that credits this to another military commander. The passage reads:

It was Colonel Alexander Rodgers of the 6th Cavalry who accomplished by taking advantage of religious prejudice what the bayonets and Krags had been unable to accomplish. Rodgers inaugurated a system of burying all dead juramentados in a common grave with the carcasses of slaughtered pigs. The Mohammedan religion forbids contact with pork; and this relatively simple device resulted in the withdrawal of juramentados to sections not containing a Rodgers. Other officers took up the principle, adding new refinements to make it additionally unattractive to the Moros. In some sections the Moro juramentado was beheaded after death and the head sewn inside the carcass of a pig. And so the rite of running juramentado, at least semi-religious in character, ceased to be in Sulu. The last cases of this religious mania occurred in the early decades of the century. The juramentados were replaced by the amucks. .. who were simply homicidal maniacs with no religious significance attaching to their acts.

5. The False Story Gained So Much Online Momentum That It Landed on a California National Guard Poster in 2005

Trump’s story reached a wider audience in the age of the Internet. It was so widespread in the days after the September 11, 2001 terror attacks, that it ended up being told by members of the government. In 2005, it ended up on a poster at the California National Guard headquarters in Sacramento and was later removed.

In October 2001, The Los Angeles Times reported that then-Senate Intelligence Committee Bob Graham (D-Fla.) recalled a dinner with people who had connections to the intelligence committee and they mentioned the story. Graham said Pergshin’s soldiers captured 12 Muslims and killed six of them with “bullets dipped into the fat of pigs.”

Graham said that U.S. soldiers wrapped Muslim rebels in pigskin shrouds and “buried them face down so they could not see Mecca. Then they poured the entrails of the pigs over them. The other six were forced to watch. And that was the end of the insurrection on Mindanao.”

Another way the story of using pig’s blood to threaten Muslims during the Philippine-American War came in a 1939 Gary Cooper movie called The Real Glory. In the film, Cooper stars as an Army doctor in 1906 Manlia who drapes pigskin around a Muslim prisoner and tells him that all killed Muslim rebels will be buried in pig skins.

Historians told Politifact that evidence that things like the incident in the Cooper movie happened is also thin. The historians told the site that Pershing tried to be a more peaceful governor compared to his predecessor, Leonard Wood.

“He did a lot of what we would call ‘winning hearts and minds’ and embraced reforms which helped end their resistance,” Lance Janda, a military historian at Cameron University, told Politifact. “He fought too, but only when he had to, and only against tribes or bands that just wouldn’t negotiate with him. He wasn’t solely committed to fighting as people like Trump who tell the pig blood story imply.”