Google DoodleBritish chemist Sir William Henry Perkin is being celebrated with a Google Doodle on what would have been his 180th birthday.

Sir William Henry Perkin, a British chemist who accidentally discovered the first synthetic dye, is being celebrated March 12 with a Google Doodle on what would have been his 180th birthday.

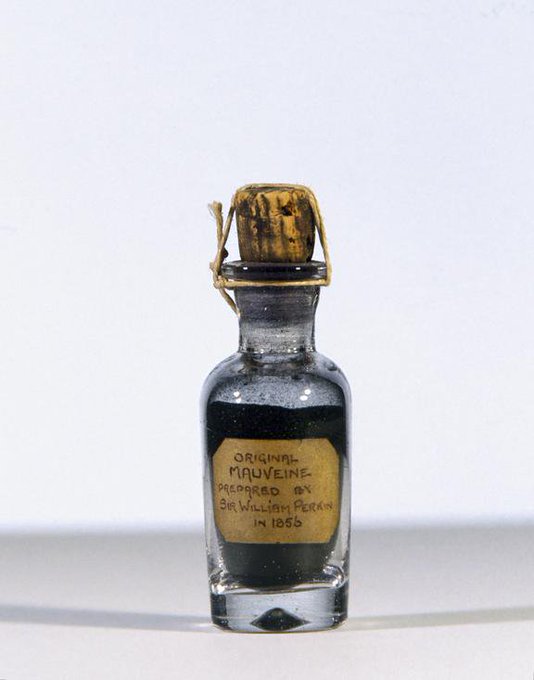

Perkin discovered the purple dye he called mauveine, which is also known as mauve.

“If you were an average person in the 1850s your wardrobe would have been made up of many shades of beige and browns. Fabric dyes were derived from plants and insects and expensive to make. Colourful wardrobes were a significant symbol of wealth; in particular purples were the often used in the garments of popes and monarchs,” the Science Museum writes. “Perkin’s synthetic colourant was a gateway, leading to the emergence of the synthetic dye industry. This is a celebrated historical story that focuses on firsts, in an industry that produced a rainbow of fantastic colours; mauve has become famous because it was the first synthetic dye.”

Here’s what you need to know about William Henry Perkin:

1. Perkin Was Born in London & Began Studying at the Royal College of Chemistry When He Was Just 15

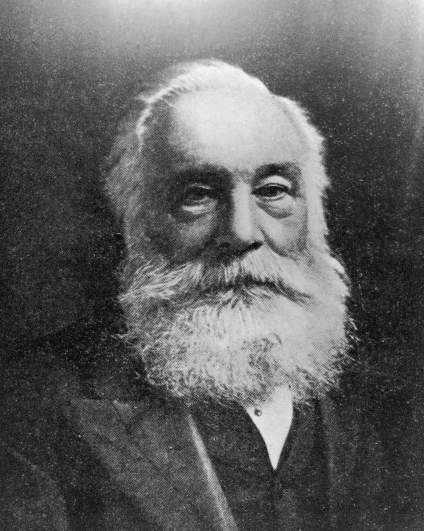

English chemist Sir William Henry Perkin

William Henry Perkin was born March 12, 1838, in the East End of London. He was the youngest of seven children of George Perkin, a carpenter, and Sarah Perkin, who was of Scottish descent, but had moved to London as a child.

Perkin attended the City of London School where he was taught by Thomas Hall, who began to help him develop his scientific talent and pushed him toward a career in chemistry, according to Oxford Reference.

“He had many hobbies, from playing the violin and the double bass to model-making, photography and painting. But, as a twelve-year-old schoolboy, he was fascinated when a friend showed him some simple experiments with crystals. He was soon skipping lunch to take extra lessons in chemistry,” according to The Victorian Web.

“Hall, was a pupil of (August Wilhelm) Hofmann at the Royal College of Chemistry and Hall pleaded with Perkin’s father to allow his son to study chemistry and not to force him into a career in architecture. Hall was successful and Perkin entered the college in 1853,” according to Oxford Reference. He was 15 at the time.

2. He Was 18 When He Accidentally Discovered the First Aniline Dye, the Purple Mauveine, While Working on a Potential Treatment for Malaria

While at the Royal College of Chemistry, which had recently been founded, Perkin became a pupil and assistant of August Wilhelm Hofmann, according to the Science Museum.

Perkin was working in a laboratory at his East London home, where he collaborated with his brother, Thomas, and a friend, Arthur Church, a painter who was interested in the chemistry of paint, in 1856 when he accidentally discovered the first aniline dye while trying to produce a treatment for malaria, the Science Museum explains:

By 1856 Perkin had become Hofmann’s assistant and (he) challenged him to synthesize quinine, an expensive natural substance much in demand for the treatment of malaria. Perkin started by reacting a salt of allyltoluidine with potassium dichromate.

The experiment failed. Repeating his method but trying different a salt, aniline, Perkin’s obtained a purple solution while cleaning out the flask with alcohol, which seemed to dye silk very easily. The colour remained in the silk even after washing the fabric.

This was the first aniline or coal-tar dye to be discovered.

According to CNN, he had used the discarded sludge from Victorian gas lighting, which was believed to have a similar chemical structure to quinine. But instead of colorless quinine, a black goo was left in his test tube, and when he tried to wash it off, a vivid purple color was left behind.

Perkin, his brother, Thomas, and Arthur continued working with the dye and eventually filed for a patent in August 1856, according to the Science Museum.

Regina Lee Blaszcyzk, a University of Leeds professor who authored “The Color Revolution, told CNN, “That industry not only brought new paints, pigments, and dyes into the world, but it was ultimately responsible for major innovations such as synthetic rubber, fibers such as nylon and polyester, and miracle drugs such as penicillin.”

Blaszcyzk added, “William Henry Perkin was no different that Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Jeff Bezos. All these entrepreneurs stumbled across an idea when they were young and unrestrained by the traditions that held back their elders, (and) were able to create something brand new — and revolutionary.”

3. Perkin Built a Successful Factory With His Father & Brothers, With Sales of the Dye Taking Off After Queen Victoria Wore Mauve to a Royal Wedding

https ://youtu.be/cuAF_3XFYDc

Perkin was able to borrow money from his father and along with his brothers started a successful factory to make the dye, Perkin & Sons.

“Various shades of purple, pink, lilac, mauve, and rose were at the height of fashion in the spring of 1856,” Regina Lee Blaszczyk told CNN. The color also got a boost because Queen Victoria wore it at a royal wedding.

The discovery of the dye was a gamechanger, according to The Guardian, because it had previously been hard to produce:

This was a big deal because, until then, purple could only be made using natural dyes and had been so expensive to make, it had become one of the most coveted colours. Because of this, purple was used to denote wealth and power.

Tyrian purple was made from the mucous of sea snails – or muricidae, more commonly called murex – and an incredible amount was needed to yield just a tiny amount of dye. Mythology states that it was Hercules himself who discovered it – or rather, his dog did, after picking up a murex off the beach and developing purple drool.

Tyre, in what is now Lebanon, was a Phoenician city on the coastline of the Mediterranean Sea where the sea snails (still) live. Amazingly, given how many were needed to sate the appetite of emperors and kings, they didn’t become extinct. The vats used to make purple sat right on the edge of the town, because the process was a stinky one. The Roman author Pliny the Elder, not easily swayed by the fashion for purple, wondered what all the fuss was about, declaring it a ‘dye with an offensive smell.’

Perkin’s dyeworks was set up at Greenford on the banks of the Grand Union Canal in London, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry.

“Perkin could not have chosen a better time or place for his discovery. England was in the midst of the Industrial Revolution and coal tar, the major source of his raw material, was being produced in large quantities as a waste product of coal gas and coke,” the Royal Society of Chemistry explains.

“After the discovery of mauveine, many new aniline dyes appeared (some discovered by Perkin himself), and factories producing them were constructed across Europe. In the pursuit of more and more colours German and British dye manufacturers pushed at the boundaries of chemical knowledge and the experimental work of the dye industry is closely linked to developments in medicine and pharmaceuticals,” the Science Museum writes.

4. He Retired a Wealthy Man at the Age of 35, but Continued His Scientific Research, Publishing More Than 60 Papers on a Variety of Subjects, Including Faraday Rotation

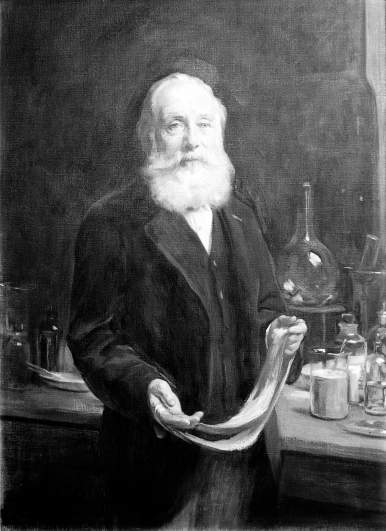

Sir William Henry Perkin.

Perkin eventually sold his factory retired a wealthy man at the age of 35 as the market for dyes became more competitive, according to Oxford Reference.

He did not, however, stop contributing to science. He wrote over 60 papers during his life after retiring from the factory, including more than 40 papers on Faraday rotation, which he became particularly interested in, Oxford Research writes.

According to The Victorian Web, Perkin was “piously evangelical, charitable, teetotal and vegetarian.”

Regina Lee Blaszcyk told CNN, “By laying the foundation for the synthetic organic chemicals industry, Perkin helped to revolutionize the world of fashion. For the first time, a schoolteacher could afford to buy beautiful calicos in printed bright colors and sew a colorful dress for herself, maybe using the new Singer sewing machine imported from America. The calico wouldn’t fade after washing or drying in the sun.”

5. Perkin, Who Died of Pneumonia in 1907, Was Married Twice & Had 7 Children, Including 3 Sons Who Followed in His Footsteps as Chemists

Perkin died on July 14, 1907, in London, of complications of pneumonia and a burst appendix. He was buried in the grounds of Christchurch in Harrow.

Perkin was married twice, first to Jemima Harriet, in 1859. He had two sons, William Henry Perkin Jr. and Arthur George Perkin. His second marriage was in 1866, to Alexandrine Caroline. He had a third son, Frederick Mollwo Perkin, with his second wife, along with four daughters. All three of his sons followed in his footsteps and became chemists. William Henry Perkin Jr. was best known for his work on the degradation of naturally occurring organic compounds. Arthur Perkin was a professor of color chemistry and dyeing.

Perkin received several honors during his lifetime, including being elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society, in 1866. He then received its Royal medal and their Davy Medal.

“He was even knighted in 1906, on the 50th anniversary of his serendipitous discovery,” according to Google.

He was awarded the first Perkin Medal, which was established to commemorate the 50th anniversary of mauve. It is now the highest honor in U.S. industrial chemistry and is awarded annually by the American section of the Society of Chemical Industry, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry.

“Fifty years after the discovery, Perkin’s work had led to the existence of 2,000 artificial colours,” the Royal Society says.