On Jan. 19, the New York Times editorial board made history when it endorsed two candidates, Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar, for president, concluding, “May the best woman win.”

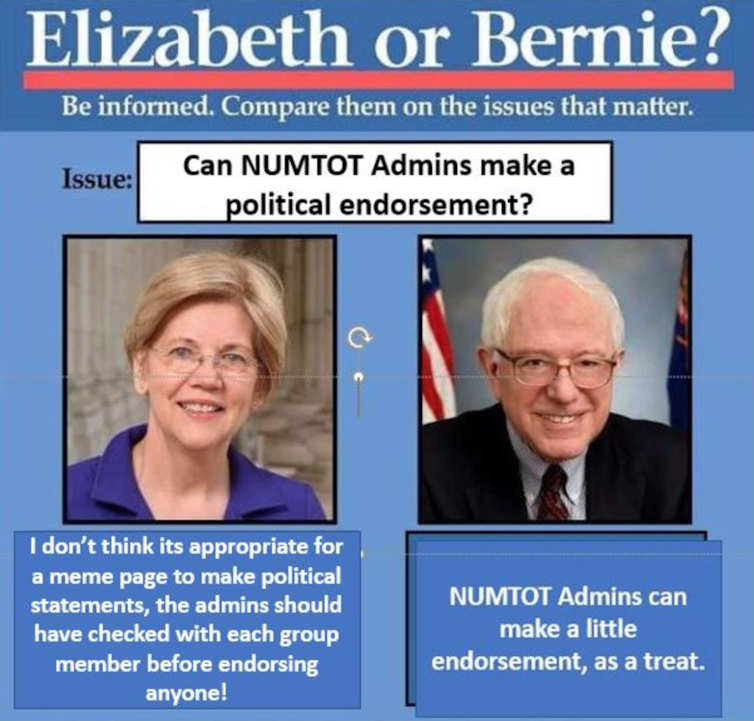

This came on the heels on another key endorsement, one that got far less media coverage: On Jan. 15, New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens, a private Facebook meme group, endorsed U.S. presidential candidate Bernie Sanders.

Within hours, Bernie personally thanked the group’s nearly 180,000 “NUMTOTs,” as they affectionately call themselves.

Why would a leading contender for the Democratic nomination so eagerly patronize a niche group on a social media site?

In 2020, it’s simply smart politics – and a sign of how campaigning and political messaging strategies are rapidly changing. Bernie’s post on the Facebook group’s page now has over 16,000 reactions and nearly 3,000 comments.

New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens/Facebook.com

As experts on political memes, we’re well aware of the ways memes and meme groups can influence politics on the sly.

Though they might seem like humorous, pithy or even nonsensical digital artifacts, memes, as our research has shown, wield the power to unite, divide, persuade and provoke voters. They’ve become an increasingly important – even indispensable – communication tool in politics, helping ordinary voters shape political debates and hone arguments from their phones.

It’s a radical departure from just a decade ago, when donors and legacy media outlets largely set the tone, defined the parameters and dictated the topics of debate.

With social media now a battleground for political debate, memes have become a key way for regular supporters of a candidate or party to unite around certain issues, generate talking points and crystallize policy platforms – regardless of what The New York Times, Fox News or The Washington Post has to say about it.

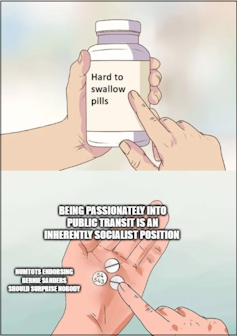

New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens is a large, diverse meme group on Facebook. Created in 2017, the page attracts those who share an interest in urban planning, housing justice, transportation infrastructure and climate change.

New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens/Facebook.com

On Facebook, thousands of NUMTOTs engage in robust democratic debate; it just so happens that much of this debate often comes in the form of Pokemon or Winnie the Pooh memes. In the past few days, NUMTOTs have debated renters’ rights, fair housing policies, flood management for densely populated areas, public transit, income inequality and shelters for LGBTQ+ youth.

But with the 2020 presidential race well underway, the group has also been discussing the candidates and their policies.

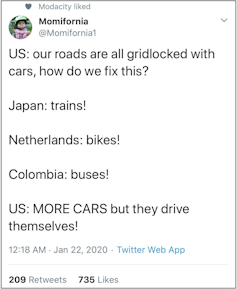

The page has an outsized ability – on Facebook, at least – to communicate members’ political positions. Endorsing Bernie could prove particularly effective for mobilizing young voters, since 90% of NUMTOT’s members are under 34 years old.

New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens/Facebook.com

One NUMTOT member pointed out recently that this group boasts the size – and, more importantly, people power – of a small city.

Research has already demonstrated how memes shaped the 2016 election. As we note in our book, memes from far-right Trump supporters effectively framed media conversations about the election, with ethno-nationalist talking points taking center stage in traditional media outlets. That may not have been the Trump campaign’s plan, but there’s no doubt that these memes funneled attention in Trump’s direction.

For his part, Trump – perhaps intuitively understanding their power – retweeted some of these viral memes, even though the meme’s creators had little or no connection to his official campaign.

Four years later, the politics of memes have evolved. NUMTOT’s endorsement actually represents an organized political decision that, in turn, has been acknowledged and celebrated by a candidate.

Not only can memes seed talking points to campaigns, but they also give candidates a window into the issues that are important to subsets of voters. Memes have become a way for political groups to coordinate and act collectively, and guerrilla imagery has become a key component of electioneering.

May the best memers win.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

By Heather Woods, Assistant Professor of Rhetoric and Technology, Kansas State University and Leslie Hahner, Associate Professor of Communication, Baylor University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.