Debora Green is the real woman behind Lifetime’s movie, “A House on Fire,” which tells the true story of a Prairie Village, Kansas doctor who killed two of her three children in a house fire and poisoned her husband, who survived. Green is now 70 years old and serving a life sentence in prison.

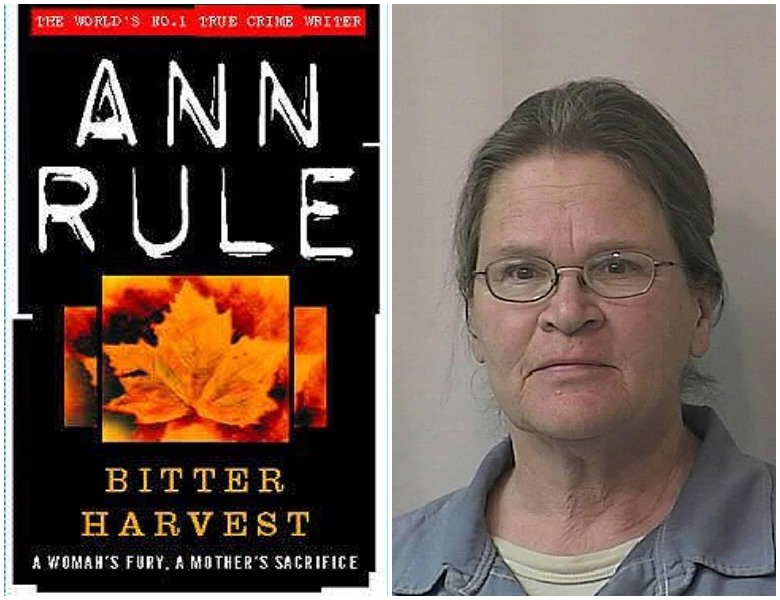

Some of the dramatic moments in the movie seem to jarring to be real. But the evidence presented by Kansas prosecutors paints a terrible picture, which included young Kate Farrar pleading with police to save her siblings, and Green telling her son to stay inside the burning house. The movie aired Saturday, March 13, 2021 on Lifetime. It was based on the true crime novel by Ann Rule, “Bitter Harvest.”

Early in the morning on October 23, 1995, Green set her family mansion on fire, killing her 12-year-old son, Tim Farrar, and his 6-year-old sister, Kelly Farrar. Her middle child, 10-year-old Kate Farrar, escaped by jumping out onto the garage roof and into her mom’s arms. Green’s husband, Dr. Michael Farrar, was spending the night with his lover. She had already poisoned him with ricin at least three times.

Green and Farrar were successful doctors. On a trip to Peru, they met Celeste Walker and her husband, Dr. John Walker. The encounter revealed the cracks in Green and Farrar’s own marriage, beginning a spiral that ended in a double murder.

Here’s what you need to know:

Green Avoided the Death Penalty by Pleading No Contest to Her Charges & Was Sentenced to Life in Prison; She Read a Statement Saying ‘I Love Her Family Very Much’

Green could have faced the death penalty if she had not entered a plea of no contest in her case, according to court filings. She was charged with two counts of capital murder, one count of attempted capital murder, aggravated arson, and one count of attempted first-degree premeditated murder. Green entered her no-contest plea April 17, 1996, and the state recommended concurrent sentences.

Green was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for 40 years. She is incarcerated at the Topeka Correctional Facility, according to her prison records.

Green read a prepared statement at her plea hearing, court filings said. She said she was out of control of herself when her children died, and said “I love her family very much.”

The statement said:

I am aware that the State can produce substantial evidence that I set the fire that caused the death of my children. My attorneys are ready willing and able to present evidence that I was not in control of myself when Tim and Kelly died.

However true that may be, defending myself at trial on these charges would only compound the suffering of my family and my daughter, Kate. I love my family very much. I never meant to harm my children but I accept the fact that I will be punished harshly. I believe that it is best to end this now so that we can begin to heal from our horrible loss.

A Police Officer Found Kate Farrar Outside Their Burning Home, Pleading With Him to Save Her Brother & Sister

The prosecution’s evidence presented in Green’s case details the real-life tragedy that occurred as the Prairie Village home was burning down with two young children inside. Kate Farrar was only 10 years old when she was able to escape her burning house by jumping off the garage roof. She knew her older brother and younger sister were trapped inside. Someone called 911 from the house, but hung up. Police and firefighters were dispatched and arrived on the scene.

There, Corporal Steve Hunt found the young girl “panic-stricken” and pleading with him to save her brother and sister.

Police interviewed Green, who was “casual and nonchalant” in police interviews. She did not ask if her children survived for about an hour. Investigators determined her son called her on the intercom during the fire, and she told him to “stay in the house and let the professionals rescue you.”

Investigators found a book in Green’s bedroom called “Necessary Lies,” which she had checked out from the public library. The plot centered around children burning to death in a fire set intentionally.

Green & Farrar Had a ‘Troubled Relationship’ & Were Discussing Divorce Following His Affair With Margaret Hacker

At the time of the fire, Green and Farrar’s relationship was falling apart. The state of Kansas presented 17 pages of evidence that was read into the record at the time of Green’s sentencing. It detailed their “troubled relationship,” divorce discussions and separation, and his affair with Margaret Hacker.

The prosecution’s evidence says Farrar moved out of their home in Missouri and separated. Later, Green and Farrar discussed reconciling and buying the home in Prairie Village. He later told Green he changed his mind about buying the house with her, but their Missouri home caught on fire May 21, 1994, and they did move into the Prairie Village home together.

Farrar told Green he wanted to divorce her in August 1995. He was having an affair with Hacker, which began in late July or early August. Green’s behavior became “erratic,” and she started drinking heavily and was unable to properly care for their children.

On August 4, 1995, she hid under a bed in their basement and called Farrar, saying she was walking down the streets of Kansas City and hoping someone would kill her.

Farrar became sick on August 11, and his condition deteriorated to the point where it became life threatening. He was hospitalized August 18 and released a week later, only to become “violently ill” within a few hours of returning home and eating. He was again hospitalized, stabilized and released August 30. He then became ill again September 4 and was hospitalized until September 11. Doctors were unable to tell what was causing his symptoms.

Investigators later determined Farrar became sick after eating food served by Green, who had a degree in chemical engineering. Blood tests indicated he had been exposed to ricin.

At this point, Farrar was staying in their home because he was concerned about Green’s ability to care for their children. He tried to have her committed to a mental institution September 25, 1995. It was then that investigators found evidence in her purse that Green was poisoning her husband. The evidence included vials of sodium chloride and packets of castor beans. She claimed it for a science project for one of her children.

Authorities found her drunk in bed when they arrived to take her for a mental evaluation. Prosecutors said she called her husband a f***hole, and told him “You will get the children over our dead bodies.”

Green Attempted to Retract Her Plea & Have Her Sentence Vacated, But It Was Affirmed in 2009 & 2015

Green filed a motion in 2004, attempting to have her no-contest plea withdrawn in the charges related to the murder of her children and the house fire. She did not present an argument on the attempted murder of her husband. In the motion, she claimed that there was not sufficient evidence to prove the fire was intentionally set. She said she entered her no-contest plea because she believed at the time the state had enough evidence to prove she was guilty.

Experts testified in the state of Kansas appeals court and said the fire was set intentionally. A United States Court of Appeals circuit judge denied the motion in a 14-page court decision.

U.S. Court of Appeals 10th Circuit Court Judge Michael W. McConnell wrote in the decision:

The state was prepared to introduce substantial evidence—none of which Ms. Green contests here—which tended to suggest Ms. Green set the fire: the inconsistencies in her testimony, her recent attempt to poison her husband, the fact that she had checked out books about intrafamilial homicide and children burning to death in an intentionally set house fire, her nonchalant behavior in her police interview, and her failure to ask the police during that interview whether her children were alive or dead for at least an hour. Thus, even if we fully credited the evidence Ms. Green introduced—evidence which, at most, suggested that the cause of the fire was undeterminable, Green, 2008 WL 2079469 at *2—it would not disturb the fact that a substantial and powerful factual basis existed to support her guilt.