Google María Rebeca Latigo de Hernández

María Rebeca Latigo de Hernández, the civil rights leader who helped advance the rights of Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants, has been honored with a Google Doodle on what would have been her 122nd birthday.

She is also sometimes known as Maria L. de Hernández. The July 29, 2018 Google Doodle was designed to illustrate Hernández “doing what she did best – using her voice to elevate and benefit her community,” Google wrote.

U.S. Representative Henry B. Gonzales once said, “She fought a big fight with a little stick.”

Here’s what you need to know:

1. María Rebeca Latigo de Hernández Was Born in Mexico and Moved to San Antonio, Texas

Hernández was born in Garza García, near Monterrey, Mexico in 1896, according to Google. She was an immigrant, moving to San Antonio, Texas, “where she became one of the leading voices speaking against economic discrimination and educational segregation that was faced primarily by women and children of Mexican descent.”

According to DevDiscourse, Hernández was an elementary school teacher in Monterrey, Mexico before moving to Texas “during the chaos of the Mexican Revolution,” along with many others.

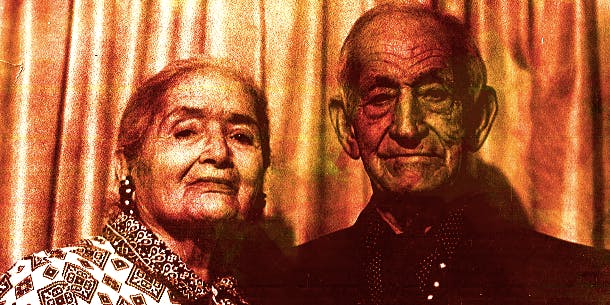

She and her husband, Pedro Hernandez Barrera, ran a grocery store and bakery in San Antonio, where they moved in 1918, DevDiscourse reports.

Her father was a professor. According to The Texas State Historical Association, her parents were named Eduardo Frausto and Francisca (Medrano) Latigo.

2. Hernández Was San Antonio’s First Female Mexican-American Radio Announcer

Hernández literally took her voice to the masses using a new medium: Radio.

“In addition to being a powerful organizer, Hernández was also a talented orator: she became San Antonio’s first Mexican American female radio announcer, and spent much of the rest of her life speaking up against injustice and inequality across both the Mexican and African American communities,” Google notes.

According to the Sun, she was also a regular on Texas television, advancing the rights of Mexican immigrants. She was described as an “untiring fighter” for the rights of Mexican-Americans.

3. Hernández Started an Organization to Educate Mexican-Americans About Their Rights

Hernández was many things; she was also a community organizer who believed in the importance of education.

Among her many contributions, “she co-founded the Orden Caballeros de America (Order of the Knights of America) – a benefit society dedicated to educating Mexican Americans about their rights,” according to Google.

She founded the group with Pedro Hernandez Barrera, her husband, on January 10, 1929.

“She also helped organize the Asociación Protectora de Madres (Association for the Protection of Mothers) which provided financial aid to expectant mothers and La Liga de Defensa Pro-Escolar (The School Defense League) which fought to replace segregated educational facilities,” Google wrote.

La Liga de Defensa Pro-Escolar was an organization “dedicated to obtaining better facilities and better education for the West Side Mexican community,” according to The Texas State Historical Association.

4. Hernández Was a Mother of 10 Children

Hernández and her husband had 10 children together. Several of their children died in infancy, however.

She died of pneumonia in 1989. She was 86. She authored an essay called “México y Los Cuatro Poderes Que Dirigén al Pueblo,” which, according to the Texas State Historical Association, highlighted the importance of mothers and the domestic sphere. She insisted on using the Spanish language in her essays, resisting the trend of assimilation.

She also served as a midwife for those who couldn’t afford medical care.

5. Hernández Fought for Workers’ & Students’ Rights

The activist was also involved in workers’ rights protests. In 1938, “she took up the cause of workers’ rights in the Pecan-Shellers’ Strike,” according to the Texas State Historical Association.

In 1939, she visited Mexican president Lázaro Cárdenas “to express good will between Mexico and the Mexicans in the United States,” the site reports.

She was also concerned about inequality in the classroom, noting inequities faced by Mexican-American children, who often had classrooms without heat and higher student-teacher ratios than non immigrant children.

“The students are not at fault for being born with black eyes and brown hair and not with blue eyes. We are all supported by the stripes and stars of the flag,” she once said. “I want you to take this gesture of this community as a protest and disgust over the terrible conditions.”